This post is part of a series.1

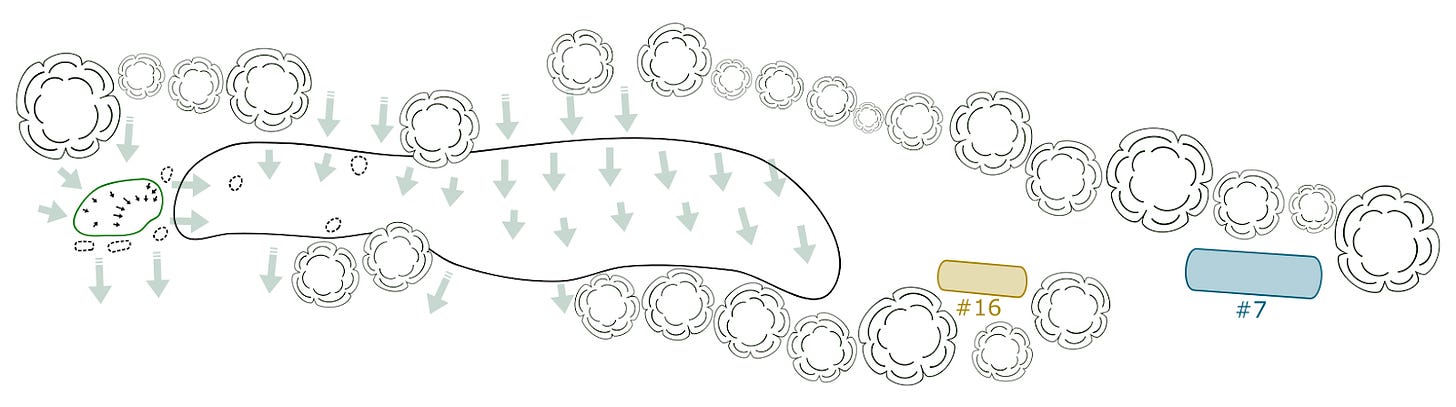

Hole 7: par 4, 352 yards.

Hole 16: par 4, 274 yards.

#7: Tunnel & Tilt

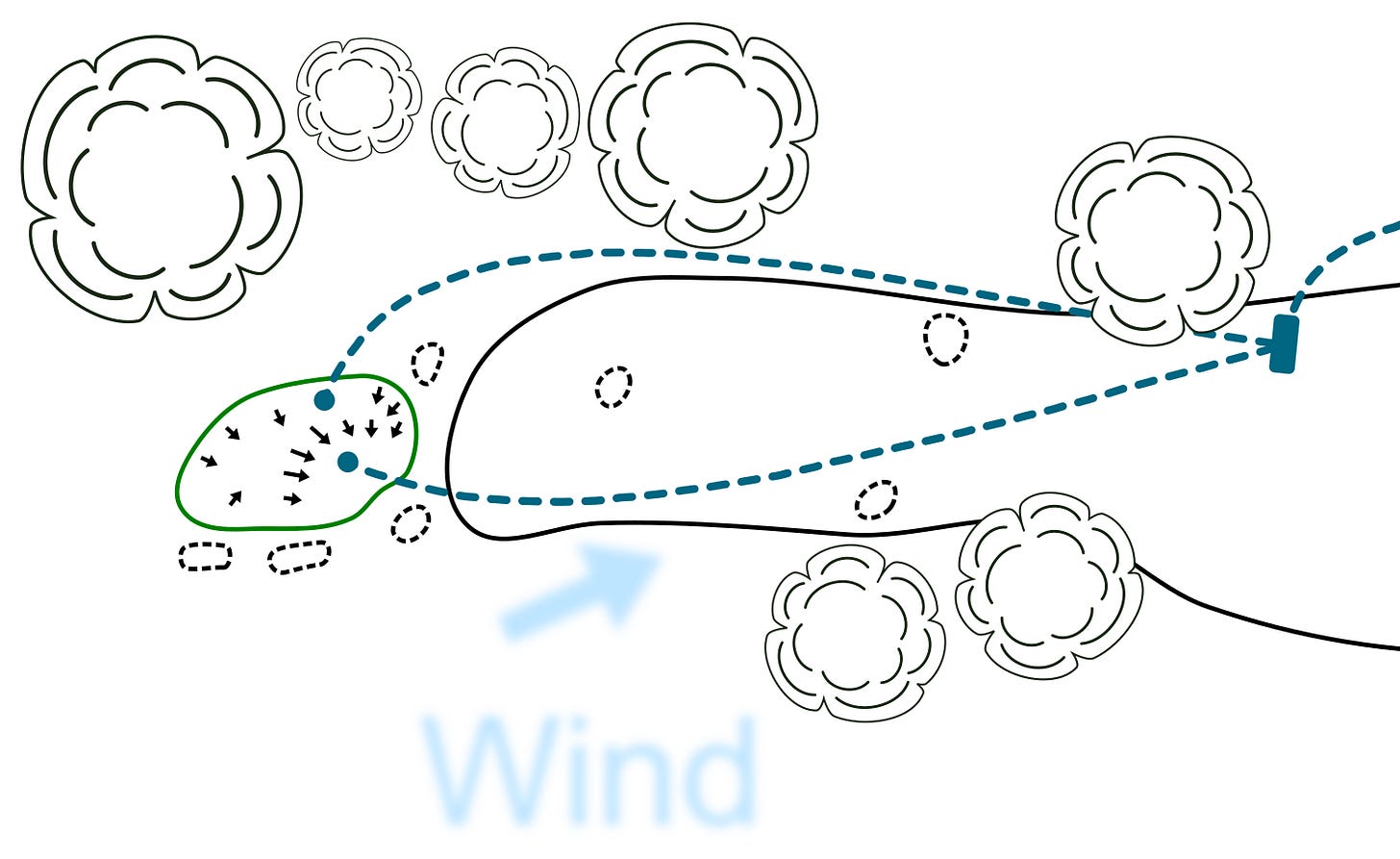

The seventh hole is classic Gleneagles. Standing on the tee, you look out over a tilted fairway, wondering how on earth you’re going to be able to hold the fairway (much less account for the wind). The drive on this hole is nothing to be trifled with. The chute through the trees funnels in the wind, which makes any mistake a disaster.

Depending on who you ask, however, these overhanging trees are a sign of a course in need of some maintenance. The main problem here is that the trees on the right block the ability for players to draw the ball into the wind — an effective strategy for just such a hole – and the trees left block the ability to hit a wide cut while compensating for the wind.

The Tilt

Errors on the drive, exacerbated by the wind, can be further punished by the topography of the fairway. The fairway itself has a noticeable right-to-left tilt. Drives either need to be shaped into the slope or aimed right to catch a kick as they come down. However players make this work, their goal should be to reach the ridge in the distance, which leaves a decent look and a better lie for their approach to the green.

The Approach

The approach shot is a big part of why this hole is so interesting. Most players, even in the center of the fairway, will have the ball well above their feet. This means the ball will have a tendency to move left, which is the more dangerous side of the green. While the green is narrow, the angle of the long green is shifted along most players’ standard dispersion shape (long-right to short-left), which should make the complicated approach just a bit easier.2 Unfortunately, if people are even a bit to the right all of this fun architecture is completely nullified by the overhanging branches of a tree on the right side.

This tree on the right here prevents players from countering the tilt of the hill by hitting a spectacular draw that wraps back along the green’s alignment. This can even interfere with some shots from the middle of the fairway. The option most will take is a layup short. However, players can either try to hit a cut from the uphill lie, a dangerous shot indeed, or try to punch one under the branches along the cart path.

The cut is the most difficult option, but if it is well executed, there is plenty of room to miss on the green’s surface and the hill behind it. The punch under the tree can be effective if it catches the cart path and runs out. If the speed is right, it should kick left and down to the green, and even a poorly struck punch has a decent chance at getting close.

The trees on the left side can also be trouble. These branches allow much more room to maneuver the ball from the fairway, but will definitely irritate left-handed players, and they will always prevent a straight shot to the green for players who end up too far left.

Thankfully most of the left side is flat. The overhanging branches will make this more difficult, but it’s a recoverable position. A low shot can run up straight to the green if the player is willing to contend with the four bunkers between the left edge and the front edge of the green.

#16: Blind Bunkers

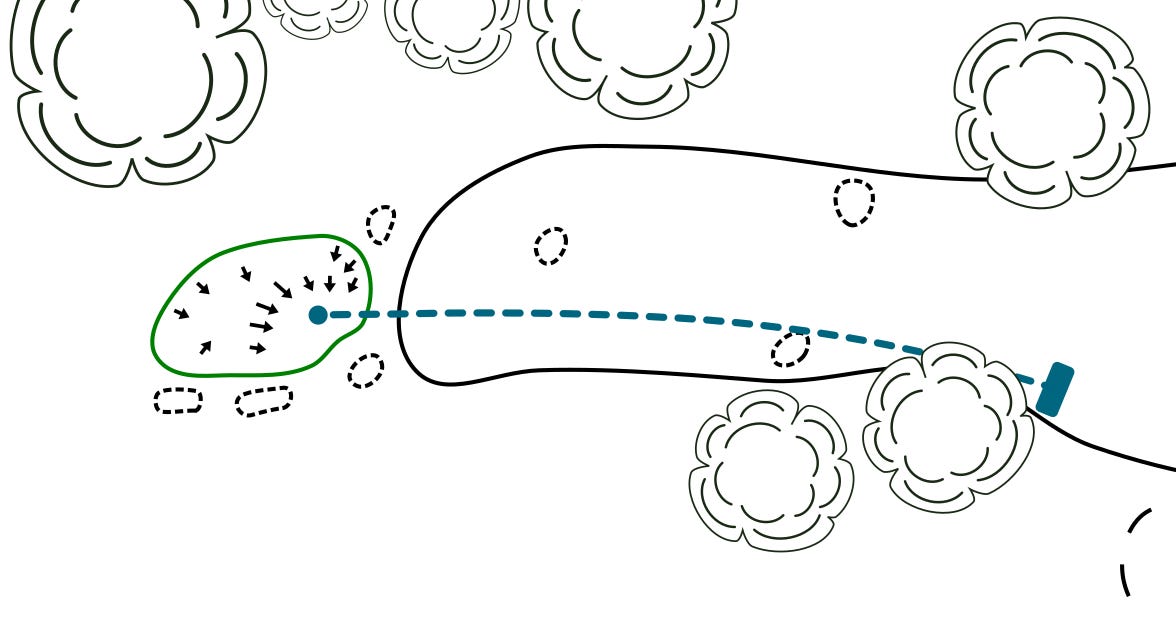

The back nine version of this hole is much shorter, but to gain this distance advantage, players must be willing to take on some risk. The new landing zone from the tee is peppered with three fairway bunkers, all of which are hidden.

Strategy: Layup

The typical strategy is simply to lay up to the #7 landing zone and play from there. The drive here is fairly simple for two reasons. First, at about 165 yards, slightly uphill, it's a relatively short shot to get a wedge in. Second, the 16th tee is tucked into an area that is less affected by the wind tunnel effect players face on the front nine, so a stock shot should play nicely.

Strategy: Send it

Players willing to take on the blind bunkers may be rewarded for two reasons. Most importantly, taking the overhanging trees out of play will prevent unlucky bounces from affecting the approach shot. Plus, for the longest hitters, there is the real chance at a putt for eagle if they can reach the green.

The fact that the long drive is a very real option on this hole truly differentiates this hole from the front nine version. Even if most people play it as a shorter version of the same hole, aggressive players will be facing a completely different challenge. This version is balanced with hazards that are effectively random and make both strategies very reasonable, thus adding optionality.3

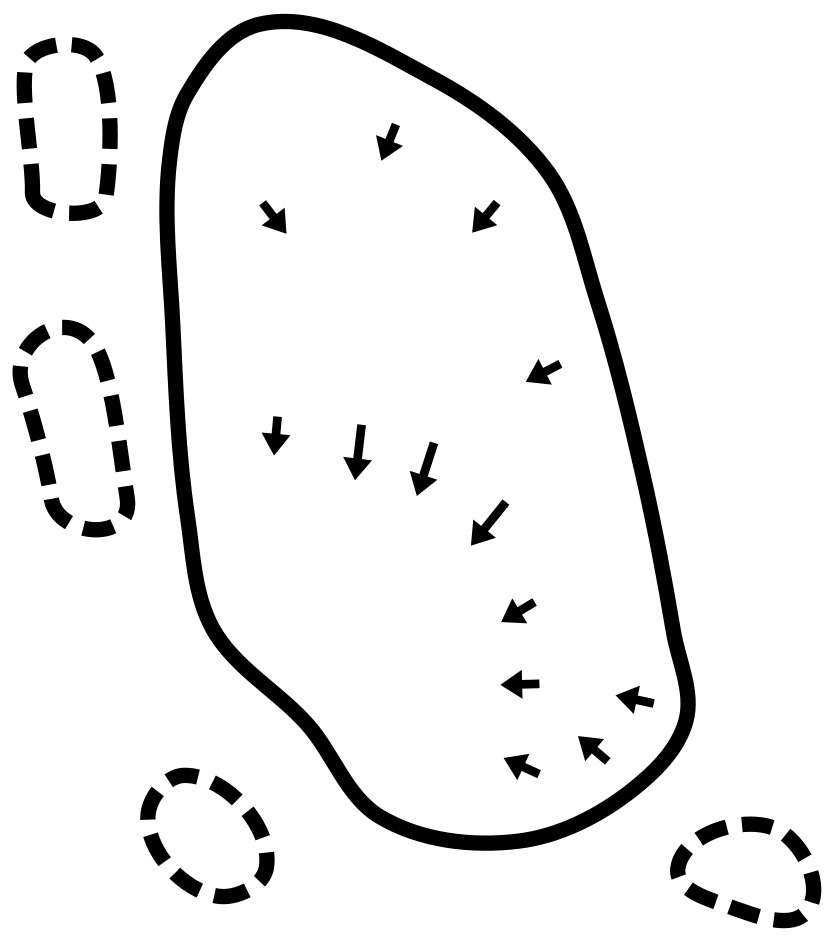

Green: Narrow With a Simple Contour

Many folks will try to kick onto the green from the right side. The big risk there is the Kikuyu. Balls can hang up in the grass there, and can be very unpredictable in the way they run down. This can make short chips more challenging than they should be.

One of the less appreciated features of this green is its slightly off-center alignment. It is long and narrow, but the back of the green has more room on the left side, and the front has more room on the right. This is advantageous to right-handers' standard miss, so it’s a bit more forgiving than at first glance.4

The biggest danger around the green is the left side. Ending up in the left-side bunkers or the tee box below is probably the worst position around the green. The front bunkers are not so bad. The green is long enough that being short-sided is usually not an issue.

Putting across this green will be fairly straightforward. There is a challenging ridge that separates the front and back of the green. The trickiest contours are in the back of the green where double breaking putts are common.

History

The most dramatic difference in this 1963 aerial image is the lack of trees on the hole. The wind tunnel is still there, but only barely. It’s effectively half as long, leaving much more room for shot shaping, and about 25% wider than where it exists today. The overhanging trees in the fairway simply aren’t there. It’s wide open, leaving ample room to attack the green from any direction.

There is also a completely different bunkering scheme in the 1963 image. The one fairway bunker existed in a very different place, threatening the drive on hole seven, not hole 16. The greenside bunker is much farther back from the green. The green itself seems to be pressed right up against the ridge where the current bunkers sit. This green site mirrors the ninth green in potentially creating a real danger of downhill putts running off the green and down the slope.

Problems

The dramatic land here, in combination with challenging winds, could make this an incredible hole on both nines. Instead, it can feel like a slog. If I were to renovate the hole, the first thing I would do is strategic tree removal or replacement. The overhanging tree on the right side is absurd; the branches invite players to try to hit a complicated shot that just as well might fly directly at the next tee box. This is dangerous and unnecessary. Columnar trees would do best on the right side to block errant shots between the holes without interfering with play on the seventh fairway.5

Next I would change the grass height, right of the green, to fairway height, letting players use the half-punchbowl to get on the green. It would be fun and have too much variance to be a reliable way to make birdie. Watching a shot run it in this way is as exciting to watch as it is for the players attempting this heroic recovery.

I would also create a gently sloping path along the far right side of the hole to ease the strain of the climb up to the fairway. It’s extremely steep in some parts, and there isn’t a route that uses the gentlest incline up the slope.

Conclusion: A Great Hole, Limited by Age

In the end, this hole plays brilliantly from the center of the fairway. It’s an epic challenge that forces people to play shots they probably don’t want to hit. At the same time it subtly bends the landing zones to make these shots a bit easier than they look. Unfortunately, the hole doesn’t always play from the center of the fairway, and there the difference between the hole being brilliant vs being a slog is a matter of a few yards in either direction.

Age and lack of maintenance have spoiled the options that this hole was created with. That isn’t to say there haven’t been any improvements over time. The uncertainty and risk of hidden pot bunkers adds a bit of linksy fun to the course. However, maintaining the width of this specific fairway is paramount because playing into a prevailing wind is extremely difficult, and adding a tilted landing zone means this challenge is magnified. People just need more room to shape their shots. A bit of tree trimming and a fairway cut from tee to green would go a long way to making this hole one of the most exciting on the course.

Other posts in this series:

#1 & #10: A deep dive into the architecture that makes this intimidating opening hole so interesting.

#2 & #11: A Switch From Strategic to Penal Architecture

#3 & #12: Down the Hill

#4 & #13: Visible and Invisible

#5 & #14: Short and Long

#6 & #15: The Old Road

#7 & #16: Wind Tunnel and Blind Bunkers

#8 & #17: Invisible Redan

#9 & #18: Contours Forever

#19: Old Peculiar’s

This type of shot supports my general theory of good golf architecture: make the easy shots hard, and the hard shots easy. I will likely write about this theory at length some day, but I’ve not fully fleshed out the idea. The general idea is that golf is the most fun when it becomes less rote and more artistic. To increase the amount of required artistry, we need to provide opportunities for extremely difficult shots, but in ways such that they have a good chance of being executed successfully. That is to say, any hazard that requires a player to “take their medicine” — simply pitch out to the fairway — removes an opportunity for a player to make a shot that is heroic and memorable. This means that hazards should be created in such a way that a reasonable unsuccessful result out of the hazard should not make the player’s position worse than it was from within the hazard.

In this example, the hazard on the right side of this fairway is the heavy (right-to-left) tilt of the fairway itself. Thus, we know that the standard miss will be left of the green. By allowing a bail-out right of the green, combined with a front-right to back-left axis along the green, we see that we allow players to embrace this miss (right-hand draw and left-hand fade) with a reasonable margin of error. This leaves them – at worst – a half shot behind the hole, which is the kind of effective penalty we would expect from the hazard itself (the heavy tilt). This shot is a reasonably hard one especially with the prevailing winds, so by adding a bit of relief to the landing area, we take away any desire for players to lay up in order to chip on.

In theory, I worry that a lot of the easing of hard shots may necessitate some handedness, and that by giving right-handed players the opportunity for a heroic shot, you necessarily make that shot near impossible for a left-handed player. But this is why my theory of architecture is not fully fleshed out. In this case, a ball-below-feet lefty fade allows plenty of room to use the hill on the right side of the green to leave a chip on, it’s just that the target needs to be the hill, with the (good) luck potential being a chance at reaching the green. Unfortunately, the overhanging tree on the right usually makes all of this moot.

I consistently argue that optionality is a hallmark of good architecture, however, people generally think of optionality as implying width. On this hole, however, the options involve tradeoffs in length in addition to a semi-punchbowl that, if cut to fairway height, would offer an alternative route to the green.

I think it’s important that the tradeoffs in distances are probabilistic, in that a longer drive should provide a real advantage to the hole – say, half a shot – while the probability of the hazards should net the advantage. In this example, we need to net half a shot. We could approach this half stroke advantage by netting it with a hole stroke penalty a third of the time (your standard red stake hazard). However, I prefer more randomly distributed, less penal hazards – that is, we net our half-stroke advantage instead with only a quarter stroke penalty, but that penalty happens only two-thirds of the time. Here, the outcome is the same, but risk-averse folks will be more inclined to lay up.

I could understand that we would want to incentivize higher risk behaviors a bit, to balance out the human propensity for risk aversion, but we want to be wary of whether this will simply result in different choices for different games. In these situations, suddenly who plays first in match play really matters.

Finally, I will say that any course that was concerned with these stochastic choices ought to keep an eye on what the players are actually playing. I realize that it’s no longer normal for a superintendent to build a bunker with a shovel and some free time, but using play data to justify increasing and decreasing the sizes of fairway bunkers could be a good way to achieve highly variable play, and to adjust for new technology.

The standard right-handed player’s dispersion is aligned long-left and short-right. A shot that draws more than intended will likely be hit with a more closed club face and travel farther; whereas a shot that over-fades will balloon a bit, and end up short-right of its target.

Columnar trees are varietals that grow tall, but narrow.