We’re Not Going to Agree on What Links Golf Means

Definitions seem easy, but nature refuses simplicity

Intro

A term that has given rise to a certain amount of controversy even in its native land is the word ‘links.’ There is a modern tendency to restrict this term to the natural seaside golf country among the sanddunes, and it is frequently suggested that the word has always been applied only to courses of this traditional type. But I can find no support for this contention. The noble expanse of turf on which the Royal Eastbourne course is laid out was known as ‘The Links’ long before anyone thought of playing golf over it, and it is high up on the downs. A similar stretch of down at Cambridge was long known as ‘The Links’ although nobody ever thought of playing golf there. Sir Walter Scott in Redgauntlet puts a definition into the mouth of the English Darsie Latimer:

‘I turned my steps towards the sea, or rather the Solway Firth, which here separates the two sister kingdoms, and which lay at about a mile’s distance, by a pleasant walk over sandy knolls, covered with short herbage, which you call links, and we English downs.’’ — Letter III.1

—Robert Browning, A History of Golf: The Royal and Ancient Game

I want to discuss here what we mean by links golf, and how the perennial fight about the term’s use impacts the greater golf community. Most folk anticipating another article confirming their priors—that it’s obvious what a links golf is—probably aren’t going to like this one. My background in language has left me perpetually frustrated with this debate, and so I thought it was worth exploring.2

But it is obvious.

Yes, the obvious answer to what we mean by “links golf” is golf on linksland. And I understand why some might respond to me like I’m an imbecile3 for questioning it. Yes, If you want to define it that way, more power to you, but this simply pushes the question to what we mean by “linksland.” Here are some of the reasons this gets complicated:

Do we mean only places historically referred to as “linksland”?

If we define linksland geologically, how wide a net do we cast?

How much construction is allowed before the linksland stops being linksland?

What if a place was once linksland, but then was, say, mined for sand?

Could former linksland be restored back to linksland?

If former linksland can be restored, can non-linksland be converted?

If we accept that geological processes define linksland, how much ecological diversity do we tolerate before we stop calling it linksland?

What if we encounter linksland with trees, and the course on linksland ends up with tree-lined fairways?

The qualities of golf on traditional linksland are worth celebrating. Almost all of the questions posed here are focused on edge cases. A good parallel is looking at what we mean by “countries.” It’s easy to point to the U.S. or Germany as obvious examples of countries, but things get complicated when you look at edge cases like Taiwan. If all we care about are the obvious cases of linksland, we could just send people to St Andrews Links and call it a day.

If someone is more concerned with links golf as a style of golf—the way the ball dances on the first bounce, the beauty of the way the shadows fall in the evening, the ability to play the game on the ground—things start to get extremely complicated. The imitation “links style” courses you see in many areas of America are pretty much insulting to anyone who has played on fescue by the North Sea. Still, modern courses designed to honestly reproduce the style of golf at these historic venues are getting extremely good. Can we protect the specialness of traditional links courses while still offering an olive branch to those good-faith actors trying to offer the experience in places far removed from where linksland occurs naturally?

Links

This is generally the part of the essay where a writer might note, “Webster’s Dictionary defines…”, but that will not serve my purposes here.4 Even the etymology of the word is generally contested if you go back far enough: Old English’s hlinc is generally cited, but also the Proto-German hlinen (some record lenk-en); still others have tied the word to Old English’s ling and Middle Engish’s linch.56 What people usually ignore here is that some of earliest references to the word tie it to both rivers and fertile soil, not just sandy coastal areas.7 None of that matters, though, when dealing with the semantics of how it is used in a modern context. I just think it’s worth pointing out so that people don’t start making historical arguments for some clear and singular definition.

Yes, all courses used to be called “links” even if they weren’t on linksland. No, that is not important for our purposes here.

Just to get it out of the way, yes, golf courses that weren’t on linksland have been called “links,” even as far back as 1712.8910 The term has been effectively used this way to the point at which our written records begin. The debate as to whether this term is or was “incorrectly” attributed to those courses is both difficult to address and is beside the point. We have multiple etymologies. The term was used to reference various courses and types of land that don’t comport with the current meaning. It is hard to argue that the term didn’t have a wider use than the one we currently maintain.11 Again, all of this is mostly irrelevant to my purposes here, but is also still worth illustrating.

Aside from casual slang, I do think we use the term now to refer to linksland, and especially golf courses on linksland, or at least it is used to imply or associate a golf course with an idea of linksland.

Linksland

I know it when I see it

The term linksland seems much more modern that the term links,12 but if we just mean linksland when we say links, then it’s still pretty simple, right? Well, again, this just punts the issue from one term to the other. Again, the idea of linksland is framed by what we mean when we say “linksland” and where we draw the boundaries of the term. The attributes that come to mind when we think of linksland are quite obvious. Foremost, there is the location; linksland sits on sandy dunes between the inland fertile areas and the beach. To many, that’s all we mean: a term defined simply by pointing at the things we mean — linksland there (St Andrews Links), and there (Yellowcraig), and there (The Links on Holy Island).1314 This is a very good way to frame a definition!15 Unfortunately, “I know it when I see it” types of definitions have trouble holding up to scrutiny. That only matters if we have strong feelings about our terms. This is semantics after all, but when we disagree about semantics, it’s generally a good idea if there is some mostly objective method to our taxonomy.

With linksland, we run into large differences in kind when we start looking at edge cases; e.g., are the mountains of sand in the Murlough Nature Reserve the same thing we mean when we talk about the subtle contours at Coul Links? How far inland is linkland allowed to be? What level of turf coverage is needed, or which species? What about areas in South England, France or the Netherlands? What about in America or Australia? Is there a point when linksland just becomes dunes?

Definitions in nature

To deal with the muddled approach of pointing at things, we usually turn to formalize concepts, but this is not without some difficulty.16 Here, thankfully we can simply point to natural systems to better define our terms. When we think of linksland, we need to think of rivers.17 Generally speaking, rivers feed the sand onto the beach, where the waves push the sand along, then wind blows the sand into coastal dunes. Now, coastal dune systems are complex, and linksland is a very general term, but if we are trying to find meaning for linksland based on natural processes, we should be able to conflate the two ideas.

Looking to coastal dune systems as a natural proxy for what we mean by linksland is fine, but it leads to more disagreement. Do we require grasses? Which types of grasses, and how much coverage do we require for the land to be considered linksland? Again, we get caught up in disagreements on the minutia, even when examples of linksland already in the accepted canon show the breadth of possible answers to these questions.18

Trouble Spots

Trees

Carnoustie

What about trees? We have some prominent links courses with some trees. Anyone can see the trees in some parts of Carnoustie. Do we concern ourselves with this? Coastal dune systems can support trees under certain situations, but I think most golfers would reject heavily forested areas as linksland, even if they are steps away from dunes like in the Gateway National Recreation Area. And Scotscraig—a course literally on a road called Linksfield—has too many trees to be considered a links by some.19

Dune structures

Bandon Dunes

Bandon acts as a shibboleth for where most traditionalists and modernists disagree. Whether all, or even some, of the courses at the Bandon resort count as links is up for debate.2021 Bandon Dunes sits on what are called Quadrinary Terraces (informally, raised beaches), atop cliffs above Whiskey Run Beach. When built, these dunes were extremely mature, and included a significant amount of tree cover. These are certainly not the same type of rolling grassy dunes found in a coastal dune system like Coul Links. But Bandon’s status as a links has faced less scrutiny than other courses, like Highland Links on more traditional linksland on Cape Cod.22 However, it is telling that while the term “links” does exist in Bandon’s marketing, they chose to use the less controversial term “dunes” in the name. As the fescue has been lost to poa, which tends to dominate other grasses in this region, some folks in the media have started to notice.23

Style

What about “parkland” courses that are steps away from beaches on dunes? This is an issue of the look and feel of a course on linksland not matching the expectations some have of a links course.

Golden Gate Park Golf Course

The most glaring example of this, to my mind, is Jay Blasi’s reworking of Golden Gate Park Golf Course on the west side of San Francisco, CA. Because the city is at the mouth of the San Francisco Bay, the west side of San Francisco used to be almost entirely sand dunes. What exists there now, especially the parks, is almost all a complete conversion of nature to suit the residents' preferences.

Slowly those dunes were replaced by roads or buildings, or were converted to parks. The city wanted these parks to look and feel like more traditional parks in other parts of the country. So they capped the dunes with soil and manure to plant trees.24 However, as part of Blasi’s reworking of the Golden Gate Park course, he scraped off the top layer of soil to get down to the dunes below. Finally, the team seeded fescue on top and Golden Gate Park GC was reborn.

While there was obviously some earth moving done, the dune system is natural and it’s as “linksland” as one could ask. The ball there dances on the fescue just like at any other links course. The problem is that it doesn’t look like what people expect a links to look like.

Grasses

Wick

Even some traditional links courses, like Wick, are poo-pooed now as no longer being “proper” links, because the wrong kind of native grasses have encroached on the playing surface25 (even when traditional grasses extend beyond fescues26).

Sharp Park

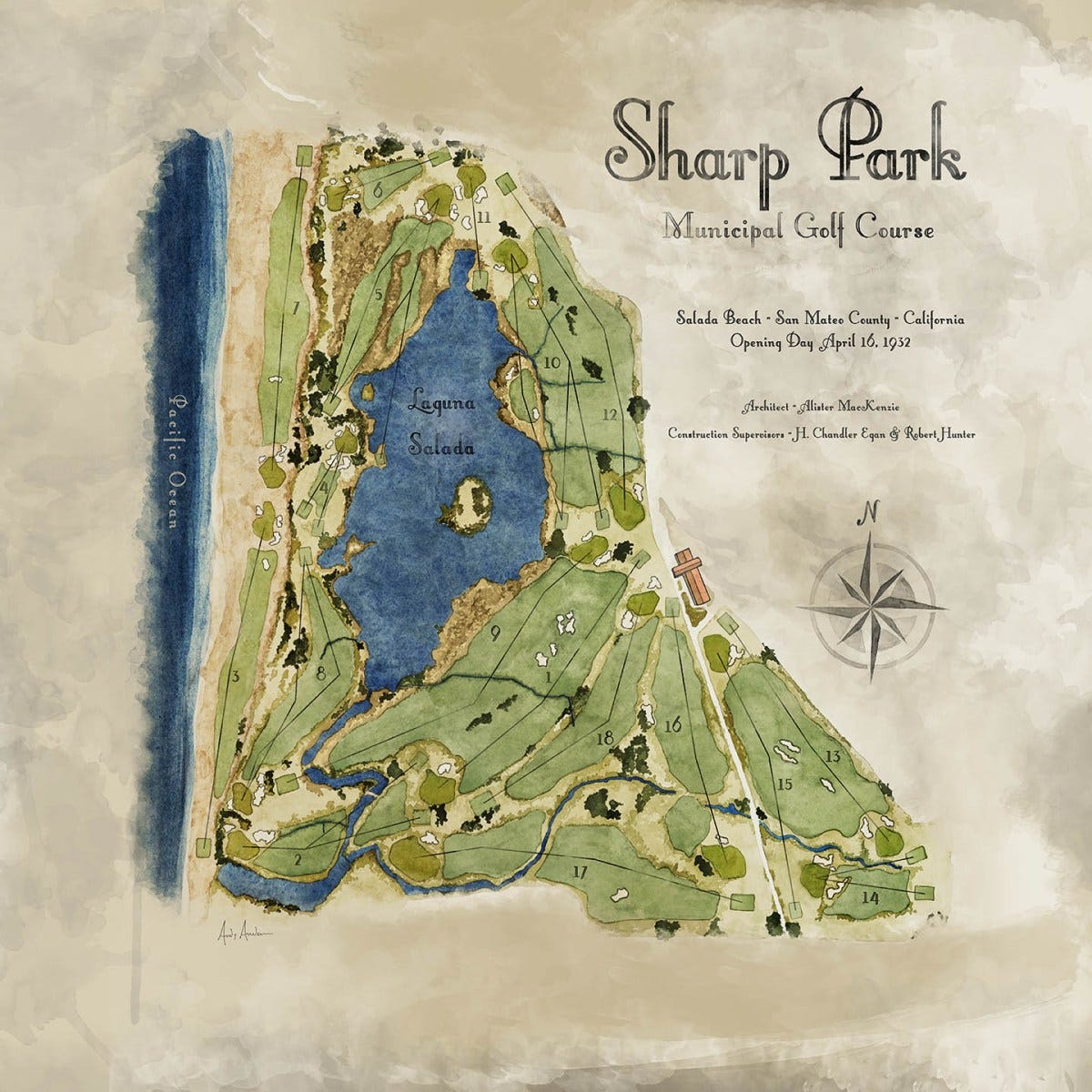

Down the road from Golden Gate Park, we get to what is left of MacKenzie’s Sharp Park:

The original version of Sharp Park, especially west of the lagoon, was as “linksland” as one can get. Built into the dune system at Sharp Park Beach, the course would over time lose its most famous holes to winter storms, the same way many links courses do. At Sharp Park, the biggest problem with a “links” designation — apart from the complications from lost holes — is the grasses. Some folks object to the invasive Kikuyu because the ball won’t run as much.

Others

There is also the Links at Spanish Bay, originally linksland that was mined for sand, after which it was constructed and grassed with fescue (later lost to poa). Because the land was mined and the grass is non-traditional, the course is often not considered a links. There is Whistling Straits, which should hit all the key requirements of linksland except that it is on the coast of Lake Michigan rather than the ocean. There is a semi-links course in Kingsbarns, not considered a links by many because some of the course was built on linksland while other parts were not, and the shaping was wholly constructed. Juxtapose that to traditional links courses like Royal Liverpool, which can completely construct new holes without concern about any Ship of Theseus problems. Finally, there are courses literally steps away from beaches, like Silverknowes Golf Course – a course that almost nobody would insist was a links course, yet one that does sit steps away from a beach.

These are all contradictions that come up when describing linksland in terms of natural systems. I’ve even heard some try to deal with these frustrations by simply claiming that only linksland in Great Britain and Ireland should count. Reaching for easy boundaries is understandable, but completely overlooks the diversity of flora across the region, while at the same time ignoring the near-identical flora of some of those areas and their neighbors in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands.27 Setting up an arbitrary distinction – say, a 475-mile radius from St Andrews to St Agnes – is just as arbitrary as “I know it when I see it.”

At the end of the day, I think the way we winnow the lists of links courses will simply differ from person to person, simply because the concept of linksland is more complex that we like to admit, and we are ultimately conflating a style of experience with complex natural processes.

One Solution: Appellations

A real testament of the vagueness of the terms “links” and “linksland” is the emergence of the term “true links”.28 Now, I’m sure there are plenty of folks out there trying to limit the term “linksland” to only the type of linksland that fits the ideas we have of links golf, and I completely understand that. The courses commonly associated with these terms are very special places, and most share extremely similar attributes. I think they are special enough to be protected, but I just think that these courses are a bit too diverse to be properly fit under one cohesive, single term.

I propose that we create well-defined appellations for all the areas that we think should qualify as linksland, and that all the courses in these regions of linksland must meet regional requirements to qualify for an official designation. The wine industry uses appellations to protect its regional wines, and so too, the golf industry could use this as a way to protect its golf regions. Assuming good-faith local control, courses like Wick could still qualify in their own region, even if their grasses vary from those on links courses in other appellations.

As an example, imagine the Tay Sandshed Links Region as an appellation. This would include all courses built on the linksland created by the sands from the River Tay. Here we could also include smaller sub-regions influenced by the River Eden’s sand.29 This Tay appellation could include courses from Arbroath to Crail, depending on the boundaries of the Tay sandshed. This is effectively a form of terroir. Beyond this sandshed, we would start to consider courses in the South Esk sandshed to the north, and the huge Forth sandshed to the south.

The benefits of having well defined links regions defined by sandsheds is that the regions could be directly associated with their unique sandscapes. The huge dunes of the Murlough Nature Reserve region would be able to market themselves specifically by their unique dune features, instead of being lumped in with the areas without as much grandiosity.

Also, in the same way we have highly respected California wine appellations, which are distinct from the more traditional French or Italian appellations, appellations for linksland in California can also flourish even with some non-traditional qualities to them. For example, these appellations could allow for intentional design to suit the dominant (if nonnative) grasses like poa, zoysia, or even kikuyu. All of the unique instances of linksland could be respected, and the different regions could vie for prominence based on their respective unique features and cultural history.

How do we deal with the courses that misappropriate the term “links”?

Finally, we come to the heart of much of the animosity. Some accepted “links” courses do not even come close in approximating the characteristics that most links courses share. Nobody is ready to throw Bandon out of the links club, but there are plenty of courses that deserve to be.30 Ironically, some of the best homages to linksland in America are nowhere close to the ocean. The Nebraska Sandhills region, and the areas around it, are home to some of the most links-like courses that exist. Here there are rolling sand dunes, thick native grasses, and fine fescues that seem to tolerate the climate quite well.

If we’re honest about addressing genuine misappropriation, but we still want to allow some appreciation of courses that recreate the attributes well, we should spend a minute examining what we want from “links golf.” The general complaint about misappropriation is about courses that look the part, but do not play the same. Here, the attributes we should focus on are more functional than aesthetic. If we imagine Marvel’s Daredevil decided to take up the game of golf: what would he notice about links vs parkland golf?

What is essential to links golf?

Is an ocean/sea necessary to the links golf experience? Probably not.

The most obvious element of links golf courses is their proximity to a coastal body of water. Whether it’s the North Sea, the Irish Sea, the English Channel, or the Atlantic Ocean, many of the traditionalists insist this is essential. I would suggest that it is not. Many of the best and most historic links have large sections where the coast isn’t even visible. Yes there are elements of being on the coast that are extremely important to the links golf experience: dunes, wind, etc. But these elements can exist away from the coast. There may be some aspects of seaside courses that affect play (perhaps the relative humidity?), but for the most part things like the views, the sounds, or the smells aren’t particularly important to the golf.

Are strong winds necessary? Yes.

I see strong winds as the most impactful aspect of the links experience on play. It’s certainly essential. This is directly related to a general lack of trees on and surrounding the site. As trees can significantly reduce the amount of the wind in play.

Is a lack of trees necessary? Generally, yes.

Aside from aesthetics, trees can diminish the strong seaside winds associated with the traditional links golf. Even if they don’t significantly encumber prevailing winds, they can block out some shot angles that might be necessary in high winds. Thus, generally speaking, a general lack of trees should be associated with links golf, even if there is plenty of space for trees to exist in moderation.

Firm turf: is sand necessary? Generally, yes.

Sand allows for easy drainage, so the turf is generally firm, even in wet weather. It’s part of the reason the ball will bounce and run, and that’s closely associated with the links golf experience. So, is it necessary in creating the elements of links golf? I think usually, but not always.

When I was growing up in Texas, many courses would get so cooked under the summer sun each year that the ground would get hard as a rock, and bounce like concrete. This surface recreated much of the bounce and run that we expect from linksland. That said, this hardpan is a temporary condition. You might be able to replicate firm turf seasonally in some areas, but if you want it consistently you’re probably going to want to play on sand.

Another problem with hardpan is that it’s difficult to play from. Unlike in sand, chipping and pitching can be very difficult from hardpan, hence the adoption of the “Texas wedge”: playing a putter from hardpan in lieu of a tricky chip. Sand is simultaneously firm and soft. That is a unique surface, and that surface is probably essential.

Firm turf: are links grasses necessary? Probably not.

Links golf is generally associated with one grass type: fescues, particularly fine fescues. The grasses are known for allowing the ball to run without getting slowed significantly on the fairway. I’ve played on fescue at multiple courses and it certainly does cause the ball to run! However, to discuss whether this behavior exists on all types of links courses, we would need to look at all the native grasses associated with links courses: marram, sand ryegrass, fescue, and bentgrass. Unfortunately, I don’t have access to these grasses, and can’t really know whether or how much difference there is in how they behave. However, for the idea we have of links golf, I think it’s safe to say that fine fescues are probably fine as a baseline to judge the experience.

Here, however, I want to push back strongly against the perception that fairways must run extremely quickly and behave similarly to the current iteration of traditional links courses. The game has changed so much in the last 50 years that it’s hardly worth looking at the average runout on modern fairways and then pretending it needs to be maximized. First off, we have mowers and agronomy that make fairways far shorter than they ever grew when the grass was managed by sheep.31 This should lead us to believe that much of the bounce and zip of the ball are a more modern aspect of links courses than we probably realize. The other reason we tend to feel like links fairways run forever is simply that modern golf equipment helps enormously. Traditional hickory drivers had dramatically lower launch angles, which should make for dramatically more interaction with the ground off the tee.32

Thus, I think we should be very skeptical about how “poorly” non-traditional turfs behave when we are actively using equipment that largely changes the way the ball is interacting with the turf in the first place. This is especially true when the turf is cut optimally for rollout and the course has appropriate drainage. Still, this is not something I’m willing to fall on my sword over. I’ve played on fine fescues and the extra runout is non-trivial and unique, but I still think we can recreate much of that experience simply by using clubs with lower launch angles and less spin.

Irregular playing surfaces? Yes, to an extent.

Probably the most notable feature on a links course is the undulating terrain. The issue here is that the level of undulation is not really set in stone. There are links courses that are wild and links courses that are relatively flat. While not every course is the Himalayas, I think it’s fair to say that undulation is essential to the game.

Riveted bunkers? No.

The last stereotypical feature of a links course I think is worth discussing is the riveted bunkers. While they are closely associated with links golf, they are not essential, and traditional hazards were simple blowouts.33 The riveted aspect actually came about as a way to reinforce the bunkers, which could be unstable in areas that saw a significant amount of play.

If we recreate the essentials, are we recreating links golf?

So I’ve identified four essential qualities (wind, sand, grasses, and contours).34 Still, some would argue that it is simply impossible to recreate links golf. Robert Hunter writes:

The true links were moulded by divine hands. Links-land, the fine grasses, the wind-made bunkers that defy imagination, the exquisite contours that refuse to be sculptured by hand—all these were given lavishly by a divine dispensation to the British. These perfect models—not of their own making—were at hand for the British designers to study and praise.35

He continues:

When we build golf courses we are remodelling the face of nature, and it should be remembered that the greatest and fairest things are done by nature and the lesser by art, as Plato truly said.36

If there is a blasphemy I’ll speak here, it’s that I just plain disagree with Hunter. Perhaps it is that they were once limited by their technology, but architects have gotten obscenely good at recreating the contours of linksland. There is no doubt that courses like Bandon, while largely constructed, are still praised by most as “true links” courses. I think we can reproduce the essential elements of links courses, with rumples cut into sand or on sand-capped soil planted with fescues, and set in largely empty areas with strong prevailing winds. Not only do I think we can do that, but I think that to some extent we should do that where it is effective.

The question becomes, though, what do we call these “genuine” recreations? The current trend is to call them dunes courses, similar to “Something Dunes” or “Something Dunes Golf Club.” Here, we could create a brandy vs cognac distinction: all cognac is brandy, but not all brandy is cognac. In the same way, all links courses would be dunes courses, but not all dunes courses are links courses. I think if we choose to use the term “dunes,” we should use it in the same way we use “links.” That is, we should call a course “Placename Dunes” or “Placename Golf Dunes” like we call courses “Placename Links.” When you name a course something like “Sandy Dunes Golf Club” then referring to it as “Sandy Dunes Dunes” seems wrong. If we follow the traditional “Placename Dunes” we could create a suitable replacement for the unique “golf links” naming convention that differentiates the place from a generalized golf course, and communicates specific information to potential players.

I understand many will be hostile to the following statement, but I also think that it should be fine to call good-faith and high-effort linksland reproduction a “links” if it hits all the essential qualities and they are reproduced well. What we mean by “links golf” seem so deeply tied to the style of golf, and the term “links” is vague enough that the term “true links” has been adopted to refer to (mostly) natural linksland sites anyway. This especially would make sense if we had a formalized appellation system with rules where a kind of subordinate appellation could be applied to non-coastal sand sites.

Trouble still remains for terminology for not-quite-fully linksy sites. What do we do about Bandon with poa? What do we call Kingsbarns? What do we call NGLA? It is complicated. For the links-like courses built on dunes, the “dunes” moniker is perfect. However, we could again see a problem of non-linksy courses on dunes then using the term “dunes” in their names, which would perpetuate confusion.

Just spitballing here

I’ve thought of a bunch of terms to throw around. Some of them are legally different in the way that other technical substitutes often riff on the legal name:37

“Landlinks,” “inland links,” or “inlinks”

“Fieldlinks” or “field links”

“Sandlinks” could be a good replacement for inland links-style courses on natural sand sites.

“Beach.” I think the name “Beach” could be a good replacement for parkland courses on the coast; “Silverknowes Beach” has a nice ring to it, associating it with the winds of a coastal course without defining it as a links course.

Many of the courses that make the most egregious appropriations of the term “links” are simply trying to communicate that the course differs from traditional parkland in some way. Those courses should have a term that communicates that. The term “parkland” is just too vague to communicate anything. There are a few terms: “heathland,” “desert,” “mountain,” and occasional hybrids like the Melbourne “sandbelt” courses, but it’s still just too few! We should have regional terms for areas like the Long Island coast, Oregon coast, California canyons, Texas hill country, and other regions of unique landforms and flora.

Normalizing appellations or expanding our taxonomy for courses could allow for much more sustainable agronomy. Instead of planting fescues on the Oregon coast and waiting for the poa to take over, we could just design these courses with poa in mind, and make the contours more severe to create more of the movement we want on the ground. We can intentionally design inland links-like courses in Texas with an emphasis on playing them during the dry summer when the ball dances wildly on the hardpan and dormant bermuda. We don’t need to try to pretend we’re recreating Scottish linksland if we have naming conventions that communicate the style that is being created using the best regional means.

Conclusion

To summarize the contentions of this paper then. Firstly, the phrase 'the meaning of a word' is a spurious phrase. Secondly and consequently, a re-examination is needed of phrases like the two which I discuss, 'being a part of the meaning of' and 'having the same meaning'. On these matters, dogmatists require prodding: although history indeed suggests that it may sometimes be better to let sleeping dogmatists lie.38

—J. L. Austin, Philosophical Papers

I wish I had a tidy solution like others have offered. I really do think the terms “links” and “linksland” just get extremely vague at the margins. The natural processes involved are not straightforward enough for a convenient definition. This vagueness does not mean just any course can be called a links, though.

A good parallel is to countries. We can all agree that France and Brazil are countries, and that California and Alberta aren’t. Anyone suggesting otherwise would be treated as crazy. Where it becomes vague is when we start talking about Kosovo, Abkhazia, Transnistria, Somaliland, or even Sealand. Even though it’s just semantics, a lot of people have strong opinions on the margins.

When people settle into a position of certainty, it’s often the result of drawing arbitrary lines. Obviously there is nothing wrong with deciding edge cases to suit one’s personal opinions, but these arbitrary distinctions lack the authority that the language police assert.

I’ve offered a few practical solutions to this problem. Primarily, I think the easiest and most thorough way to create precision is to adopt formal, regional appellations in golf. Appellations based on sandsheds and flora provide the precise expectations on the golf experience, while allowing enough variation in local ecological regions to remain distinct. They also provide more room for wider usage of general terms, such as inland links (or links-style) courses, because the lack of appellation status communicates lack of formal recognition.39

Courses that grew out of natural linksland and native grasses are certainly special, and are certainly worth recognizing, but anywhere the wind whips, the turf bounces, and the contours are unpredictable will always be a good place to have a match, regardless of whether that place is, as Peter Alliss would say, “in sight and sound of the sea.”

Browning, Robert. A History of Golf: The Royal and Ancient Game. London : J.M. Dent & Sons, 1955, pp. 25.

My focus in graduate school was Philosophy of Language. The two subjects I wrote extensively on were ambiguity and conversational implicature. My expertise is somewhat limited, however, after leaving academia amid the 2007 start of the financial crisis. I’d add that a lot of the issues discussed here, as far as I know, are not settled, but the general points should be straightforward.

Here I must start the dive into Philosophy of Language. This will certainly not appeal to many, but how we use language will be more important to my argument than the “correctness” of the language that we use. The “imbecile” comment is a direct reference to J. L. Austin and how he presumes most people would respond to this subject:

Faced with the nonsense question 'What is the meaning of a word?', and perhaps dimly recognizing it to be nonsense, we are nevertheless not inclined to give it up. Instead, we transform it in a curious and noteworthy manner. Up to now, we had been asking 'What-is-the-meaning-of (the word) "rat"?', &c.; and ultimately What-is-the-meaning-of a word?' But now, being baffled, we change so to speak, the hyphenation, and ask 'What is the-meaning-of-a-word?' or sometimes, 'What is the "meaning" of a word?' (i. 22): I shall refer, for brevity's sake, only to the other (i. 21). It is easy to see how very different this question is from the other. At once a crowd of traditional and reassuring answers present themselves: 'a concept’, 'an idea', 'an image', 'a class of similar sensa', &c. All of which are equally spurious answers to a pseudo-question. Plunging ahead, however, or rather retracing our steps, we now proceed to ask such questions as 'What is the-meaning-of-(the-word) "rat"?' which is as spurious as 'What-is-the-meaning-of (the word) "rat"?' was genuine. And again we answer 'the idea of a rat' and so forth. How quaint this procedure is, may be seen in the following way. Supposing a plain man puzzled, were to ask me 'What is the meaning of (the word) "muggy"?', and I were to answer, 'The idea or concept of "mugginess" or 'The class of sensa of which it is correct to say "This is muggy" ': the man would stare at me as at an imbecile. And that is sufficiently unusual for me to conclude that that was not at all the sort of answer he expected: nor, in plain English, can that question ever require that sort of answer.

Austin, J. L. Philosophical Papers. Oxford University Press, London, 1961. Pages 26-27. Available on Archive.org, here.

The discussion of meaning via dictionaries is akin to the discussion of political boundaries using maps. It gets the causal relationship backwards. The purpose of the dictionary is to reflect, not define, the language. Thus, citing the dictionary when seeking the underlying meaning of contested terms is typically as much a waste of time as looking at a map to determine the political boundary of a contested region.

Etymonline. “links (n.)”. Etymonline.com, updated on September 28, 2017. Accessed Jan 2005. See also “lean (v.)” and “link (n.3)”.

I should note that the information found on Etymonline seems to come directly, or at least tangentially, from John Jamieson’s An Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language.

Jamieson, John, et al. An Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language: To which is Prefixed, a Dissertation on the Origin of the Scottish Language. N.p., A. Gardner, 1880. p. 154. Available on Archive.org, here.

Here is the full entry from An Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language:

LINKS, s. pl. 1. The windings of a river, S.

“Its numerous windings, called links, form a great number of beautiful peninsulas, which, being very luxuriant and fertile soil, give rise to the following old rhyme :

“The lairdship of the bonny Links of Forth,

Is better than an Earldom in the North.”

Nimmo’s Stirlingshire, p. 439, 440.

2. The rich ground lying among the windings of a river, S.

Attune the lay that should adorn

Ilk verse descriptive o’ the morn ;

Whan round Forth’s Links o’ waiving corn

At peep o’ dawn,

Frae broomy knowe to whitening thorn

He raptur’d ran.

Macneill’s Poems, ii. 13.

3. The sandy flat ground on the sea-shore, covered with what is called bent-grass, furze, &c., S. This term, it has been observed, is nearly synon. with downs, E. In this sense we speak of the Links of Leith, of Montrose, &c.

‘‘Upoun the Palme Sonday Evin, the Frenche had thameselfis in battell array upoun the Links without Leyth, and had sent furth thair skirmishears.” Knox’s Hist., p. 223.

“In his [the Commissioner’s] entry, I think, at Leith, as much honour was done unto him as ever to a king in our country.—We were most conspicuous in our black cloaks, above five hundred on a braeside in the Links alone for his sight.” Baillie’s Lett., i. 61.

This passage, we may observe by the way, makes us acquainted with the costume of the clergy, at least when they attended the General Assembly, in the reign of Charles I. The etiquette of the time required that they should all have black cloaks.

“The island of Westray—contains, on the north and south-west sides of it, a great number of graves, scattered over two extensive plains, of that nature which are called links in Scotland.” Barry’s Orkney, p. 205. ‘Sandy, flat ground, generally near the sea,’ N. ibid.

4. The name has been transferred, but improperly, to the ground not contiguous to the sea, either because of its resemblance to the beach, as being sandy and barren ; or as being appropriate to similar use, S.

Thus, part of the old Borough-muir of Edinburgh is called Bruntsfield Links. The most probable reason of the designation is, that it having been customary to play at golf on the Links of Leith, when the ground in the vicinity of Bruntsfield came to be used in the same way, it was in a like manner called Links.

In the Poems ascribed to Rowley, linche is used in a sense which bears some affinity to this, being rendered by Chatterton, bank.

Thou limed ryver, on thie linche maie bleede

Champyons, whose bloude wylle wythe thie

watterres flowe.

Elin. and Jug., v. 37, p. 21.

This is evidently from A.-S. hlinc, agger limitaneus ; quandoque privatorum agros, quandoque paroecias, et alia loca dividens, finium instar. ‘‘A bank, wall, or causeway between land and land, between parish and parish, as a boundary distinguishing the one from the other, to this day in many places called a Linch ;” Somn.

According to the use of the A.-S. term, links might be q. the boundaries of the river. But, I apprehend, it is rather from Germ. lenk-en, flectere, vertere, as denoting the bendings or curvatures, whether of the water, or of the land contiguous to it.

Sir J. Sinclair derives links ‘‘from ling, an old English word, for down, heath, or common.” Observ., p. 194. But the term, as we have seen, is sometimes applied to the richest land.

I think it’s important to note the various use cases here. First and foremost, I find it specifically interesting in the immediate reference to “bent-grass” and “furze” (gorse), and not fescue. While fescue may be surmised to be part of the “&c” (etcetera), in my mind, links are so closely associated with fescue that this entry was generally shocking.

The other specific point of interest is in the repeated use of the term being associated with rivers. Linksland, as we will see, is highly associated with dunes that are created from sand that is carried by rivers. I’m left to wonder whether the two are ultimately intertwined for the same geological reasons that dunes and rivers are linked.

Curiously, the idea that “links” here is most associated with fertile soil is extremely unexpected. It is pretty much the opposite of what I expected to find.

Jamieson’s first and second definition.

Jamieson’s forth definition. It should be noted here that the “Bruntsfield Links” is not the current location of the Bruntsfield Links Golfing Society. It is the Bruntsfield Links near the Meadows in Edinburgh: a large pitch and putt course. However the pitch and putt layout is not the course being referred to, as it was a six-hole course. The original course layout can be seen on the Bruntsfield Links Golfing Society’s history page.

It is also clearly marked on the map, figure 3: Plan of the Environs of Edinburgh & Leith. While undated, the map was part of a collection of maps dated 1710, “'Handed over to Lieut. [Monier] Skinner Rl Engineer by his father in 1872'. I.G.F. stamp” (full map here, more info in this PDF).

We can go back to 1711 using the term “Links” for golf courses that were not on linksland. The Bruntsfield Links is referenced in 1720 in a book of poems by Allen Ramsay in “Elegy on Maggy Johnston, who died Anno 1711.” Obviously the poem here technically can only be dated to 1720, but the usages likely dates to before 1711, given the context of the poem:

When in our Pouch we fand ſome Clinks,

And took a Turn o’re Bruntsfield Links,

Aften, in M A G G Y’s, at Hy-jinks,

We guzl’d Scuds,

Till we cou’d ſcarce wi hale out Drinks

Caſt aff our Duds.

Ramsay, Allan. Poems. Mercury, Edinburgh, 1720, pp. 26. Available on Google Books, here.

There is a published article about the poem by Adam Fox that sheds significant light on the dates involved:

Fox, Adam. 'The first edition of Allan Ramsay’s elegy on Maggy Johnston', Scottish Literary Review, vol. 11, no. 2, 2019, pp. 31-50. Available from the University of Edinburgh via this PDF.

From Fox’s footnote:

As Ramsay explained in his footnotes of 1721, Bruntsfield Links were ‘fields between Edinburgh

and Maggy’s, where the citizens commonly play at the gowff’: Poems (1721), 17n.

ScottishGolfHistory.org has a history of the Bruntsfield links (which references Ramsay’s poem and also has a map of the old course routing), but after the first reference, all their other citations come from after 1711. I can’t find a reference before this one, aside from their 1695 reference, which does not appear to name the site.

Still, nearly 170 years before Jamieson’s etymologies, the term “links” was used trivially to refer to golfing sites. While Jamieson seems insistent that this is an incorrect usage, should we not hold a bit of skepticism? We’ve gotten to the edge of recorded history here, and the folks are calling the Bruntsfield site a links.

The farthest back I can even find the word “links” or “linkes” in association with a known golfing location is from 1586 (though note that this is not a scholarly article, and I have not put as much rigor into research as I’d have liked to):

In the meane time, there was an armie prepared in England, of ſeuen or eight thouſand men, who were ſent into Scotland; the lord Greie of England being appointed generall, who come to the linkes, beſide the towne of Leith, on ſaturday the first of Aprill. Before they pitcht downe their field on the ſaid linkes, monſieur Partigues, coronell of the French armie, iſſued forth of Leith with nine hundred harqubuſſiers of Frenchmen, to a little knoll called the Halke hill, where a ſore, continuall, and hot ſkirmith was begun betwirt the Engliſhmen and Frenchmen, with hagbuts, calaeuers, and piſtolets, which ſkirmiſh continued fiue or ſix houres…

Fleming, Abraham, et al. The First and Second Volumes of Chronicles, Comprising 1. The Description and Historie of England, 2. The Description and Historie of Ireland, 3. The Description and Historie of Scotland. United Kingdom, Printed in Aldersgate Street at the signe of the Starre, 1586, pp. 372. Available on Google Books, here.

I can find the word used, but no in relation to a known location in 1541:

The. iiii. thynge is, we ſhulde eſchewe gunges, linkes, gutters, channels, ſtynkynge ditches, and al other particular places that are infected with carreyne, and places where as deed carkeſes or deed folkes bones are caſts, and places where hempe and flace watered.

Paynell, Thomas, translator. Regimen Sanitatis Salerni. 1541, pp. 14. Available on Google Books, here.

Here, as I enter the 1500’s in my research, the current computer vision algorithms start running into problems, as the letter “s” takes the form of the long s, which is often mistaken for “f” which, and occasionally the r rotunda, combine with many of the text using blackletter typefaces, makes the research infinitely more difficult. And, while I would love a research position at some university to study this stuff indefinitely, the amount of time I’ve spent on this has already wildly exceeded the amount of attention this article will get.

Browning’s references inland “links” existing in Eastbourne and Cambridge, both predating golf in their respective areas, and I’ve been able to confirm both of them:

Eastbourne:

Taking the road inland from the Holy Well, we pass through Meads, or Meads Street, a collection of cottages and farm - buildings of picturesque appearance, at the foot of the lofty hill. Here is Meads Lodge, the residence of R. M. Caldecott, Esq. From this spot the road commands a fine sea view. If we take the path in front of the farmhouse on our left, as we turn towards South Bourne on the right, and cross the field, we shall arrive at the Links - a wide undulation of soft green sward, across which is a pathway leading to Eastbourne Old Town.

Gowland, T. S. The Guide to Eastbourne and Its Environs. Sixth Edition. T. S Gowland, Eastbourne, 1863. Page 16. Available on Google Books, here.

Gowland's book also features a map (figure 1, above) that apparently identifies the location of the links, which I’ve included above, but I could not find an image of high enough quality to confirm. You can see the current site in figure 4, above.

Cambridge:

Two documents reference the existence of a “Links” in Cambridgeshire, between Cambridge and Newmarket:

Urban, Sylvanus. Gentleman’s Magazine. Volume 23. John Bowyer Nichols and Son, London, 1845. Pages 25-28. Available on Google Books, here.

IN the month of August 1842 I had the opportunity of making some notes, founded on personal inspection, of the structure of that very remarkable ancient military earthwork on Newmarket Heath, in Cambridgeshire, popularly called the Devil’s Dyke. As I am not aware that any particular survey of this strong and very extensive line of defense has been make, the report of my examination of it may not be unacceptable.

I surveyed it at a spot called The Links, where it remains very bold and perfect, about a quarter of a mile south of the turnpike gate, which stands where it is crossed by the high road from Newmarket to London and Cambridge.

(Urban 25)

Map cited above (figure 2) is from Page 26 of this citation.

I have hitherto omitted to mention, that I observed some fragments of Roman tile scattered near the dyke, and it appears to have been cut through in forming the present high road from Newmarket to Cambridge. That is some evidence for its very high antiquity. I recommend the explorator of this interesting fortification not to fail to visit the dyke at the Links, to descend into the foss, and obtain the view I have given of its course, ascending the rising grounds southward in the directions of Wood Ditton.

(Urban 28)

The Journal of The Household Brigade For the Year 1863. Edited by I. E. A. Dolby. W. Clowes and Sons, London, 1863. Page 129. Available on Google Books, here.

The Duke of Cambridge, Lord George Manners, General Hall, Colonel Macdonald, and Colonel Newton shot over the Links preserves, near Newmarket, and make a bag of 636 head—vis., 322 pheasants, 256 hares and rabbits, and 48 partridges.

The modern location of this site can be seen via the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, here, or on Google Maps, here.

There is even an adjacent golf club, called Links Golf Club.

Or “links land.” Google’s Ngram Viewer shows effectively no reference to “linksland” before 1900 (here). The viewer shows significantly more references to “links land” dating back to 1850 (here), but it’s important to remember that the vast majority of these references is to phases that end with “links” followed by other phrases that start with “land.” Most of these are legal documents.

However, here is a reference from 1865 that does use “links land” in the way we think of it:

Do you grow potatoes on all the fields on your farm?—Except the links land. I never attempt it there, because they scab upon sandy land.

Miller, William. John Sturrock. Report of the First and Second Trials of the Issue in the Action of Damages at the Instance of William Miller. W. Burness, Edinburgh, 1865. Page 219. Available on Google Books, here.

A significant amount of the thought process about language here comes form J. L. Austin, as previously referenced:

Austin, J. L. Philosophical Papers. Oxford University Press, London 1961. Available on Archive.org, here.

Some of the ideas are drawn from W. V. Quine. Particularly the concept of the indeterminacy of translation when applied to one’s own language. The idea here is that referents to words and the inherent meanings of those words suffer from an ambiguity. The main example in Word and Object is about what we mean when we say “rabbit.” When we say “rabbit” could mean the rabbit as a whole, or as all the rabbit parts connected and living. Obviously may seem a bit absurd, but the point is that there is an ambiguity that exists here because there we can create an equivalence. That ambiguity, if we consider it valid, is inseparable from thought. Thus, in a sense, language is ultimately just pointing at things without the ability to convey a complete underlying meaning:

Quine, W. V. Word and Object. Cambridge, M.I.T. Press, 1960.

Here “language as pointing at things” avoids the pitfall that language will certainly bring us:

If we rush up with a demand for a definition in the simple manner of Plato or many other philosophers, if we use the rigid dichotomy 'same meaning, different meaning', or 'What x means', as distinguished from 'the things which are x', we shall simply make hashes of things. Perhaps some people are now discussing such questions seriously. (Austin 42)

The issue of whether or how we should look into Platonic-style forms is a major point of disagreement in philosophy of language. Without getting too into the weeds. In Philosophical Papers, the first chapter is “Are There A Priori Concepts” and well it is too technical to get into here, it’s still a reasonable discussion on the subject for anyone interested.

Ironically, it is rivers that supply the vast majority of sands onto our beaches (see: How Does Sand Form? from NOAA). In doing the research for this piece I ran into some citations that did not seem to focus on this fact:

Linksland begins with a collision between sea and rock, which creates sand. Strong winds move the sand and disperse it into beaches. When grains of sand run into obstacles, they come to rest in hummocks. The longer these nascent landforms survive, the more vegetation they can support. Turf grasses like bent or fescue take hold. The rumpled topography becomes stronger, more fixed in place, and a golf-friendly system of sand dunes may emerge.

I lifted this narrative from a book called Sand and Golf: How Terrain Shapes the Game. It’s a study of sandy, windy landscapes—how they gave rise to golf and how they might continue to inspire golf course design. The book’s author, George Waters, has spent years walking and examining the links, caddying at Royal Dornoch and working on sandy sites at Barnbougle Dunes and Pinehurst No. 2.

Morrison, Garrett. “School of Golf Architecture, Part 2: Linksland.” Fried Egg Golf, 24 March 2020. Accessed 31 January 2025.

The sand is fed by rivers, and the beach becomes a kind of “river of sand” itself. Obviously this is an oversimplification, but if we intend to understand the natural processes that is linksland, at least a bit of beach and shoreline processes is necessary. Obviously wind is crucial to the creation of dunes, but the wind isn’t just blowing sand on top of them. There is suspension, saltation, and surface creep and they all occur in dune formation.

You need only look at views of the Murlough Nature Reserve or Slufter noord to see how uncovered some linksland can be, especially when compared to areas effectively covered in turf, like Achill Island.

Peper, George, and Malcolm Campbell. True Links. Artisan, 2010. Preview available on Google Books, here.

This citation is from page 20.

Some folks seem to put the courses at Bandon Dunes as effectively the only links courses in North America:

DeSmith, David. “Links Courses of The Americas: The Few, the Proud, and the Imposters.” LINKS Magazine. Accessed 1 February 2025.

The irony of LINKS Magazine publishing this is that, while the article is undated, we can use the wayback machine to see that it was probably published around August 2020. However, in 2024, Club TFE wrote explicitly about the fact that Bandon had basically lost their fescue to poa some time ago:

Over the years, Bandon has fought poa annua invasions of its fescue greens and surrounds. I am by no means an agronomy expert, so I will keep my observations broad. From what I’ve gathered by speaking with experts, there’s no stopping poa in Bandon’s landscape and climate. Fescue greens can thrive for a few years after construction, but then the poa starts to move in. Rather than fighting this evolution (or devolution) with excessive chemicals and labor, the resort has decided to concede to Mother Nature and allow the greens on its older courses to transition into full poa. This has permitted Bandon to proceed with minimal inputs, which is obviously important, but it’s not ideal from a golfing perspective.

Johnson, Andy. “Design Notebook: Bandon Dunes at the Quarter-Century Mark.” Club TFE, Fried Egg Golf, 6 May 2024, . Accessed 1 February 2025.

The fervency of some outlets is telling: ascribing the links designation to (only resort) courses that have likely been overgrown with poa a long before their articles were written. The same folks who tout grass-specific definitions of links courses either care more about the look of the course than how it plays in their definition, or it doesn’t actually influence play enough for anyone to notice. Though, I’m entirely unsure of why LINKS would even suggest that Bandon is a resort with links courses when the definition that they reference includes “indigenousness” of the grasses as a requirement, when none of the grasses listed are indigenous to coastal Oregon.

This note may not apply to the authors of True Links, who published their book in 2010 asserting that the courses at Bandon were links courses.

It is arguable that the fescue in 2010 had not been lost to poa, but honestly who knows. Some still report that that Bandon still “uses fescue extensively”:

The use of fescue grass can be polarizing among superintendents. Many top courses—like Bandon Dunes, Whistling Straits and Sand Valley—use fescue extensively, while others, notably Erin Hills and Chambers Bay, have moved away from it in recent years.

Powell, Drew. “Why some top American courses are using this ‘sustainable’ links golf feature.” Golf Digest, 17 July 2024. Accessed 3 February 2025.

Other folks have effectively suggested that Bandon simply is not a links at all:

There may not be a better opening tee shot in the game than the first volley at Pacific Dunes. The original Bandon Dunes fits into the land like it was carved from the hand of Donald Ross himself. Old MacDonald, the newest edition to the Dunes family, has been dubbed the best of the bunch.

None of the three, however, is a true links course.

Hoggard, Rex, and Erik Peterson. “Did Bandon Dunes bring Scotland golf to America?” Golf Travel Insider, The Golf Channel, 12 July 2010. Accessed via Archive.org on 1 February 2025.

DeSmith states in “Links Courses of The Americas: The Few, the Proud, and the Imposters”:

It should be said that there are many courses in The Americas that look and play like links courses. If you can’t make your way to Oregon or Nova Scotia, here are a few that offer very enjoyable near-links experiences.

Followed by:

• Highland Links (9 holes) – Truro, Mass.

Johnson, Andy. “Design Notebook: Bandon Dunes at the Quarter-Century Mark.” Club TFE, Fried Egg Golf, 6 May 2024. Accessed 1 February 2025.

Found SF. “Turning Sand Into Golden Gate Park.” FoundSF. Accessed 31 January 2025.

Peper 20

Grasses commonly associated with links courses: ammophila (marram grass/bent grass), leymus arenarius (sand ryegrass/sea lyme grass/lyme grass), festuca (fescue), and agrostis (bent or bentgrass).

Much of this article sprung from a discussion I participated in on Golf Club Atlas: So why do we love Links golf?. Here the claim was made by multiple people that linkland was only really linksland if it was on the Great Britain and Ireland archipelago. I obviously find this perfectly ridiculous.

The term “true links” is thrown around so much, there is even a book:

Peper, George, and Malcolm Campbell. True Links. Artisan, 2010. Preview available on Google Books, here.

The term is effectively a response to the proliferation of “links” courses that do not suit any of the necessary or preferred attributes of a “links” course. Ironically, while this term may intend to clarify, it dances dangerously close to a “No True Scotsman” fallacy in that it defines away any potential counter examples.

As an aside, while I do not want to delve too deeply into this corner of semantics, True Links may be one of the most maddening sources to read during this period of research. The authors rapidly go from authoritative:

Instead, a modern meaning has taken hold, a definition not of links per se but of linksland, the ground on which a proper links course unfolds. (Peper 4)

To refreshingly open to alternatives uses:

Can a bona fide links course take the form of any other sort of terrain? Our answer is a qualified yes. Clearly man cannot create true linksland—Mother Nature needed centuries to do that. Nor can man create the climate and wind conditions that distinguish a genuine links. However with a conducive site and sufficient resources, man can replicate the experience of links golf—indeed, create a links course—on nonlinksland. (Peper 14)

To then be downright exclusionary:

Proximity to the sea would seem to be an artificial sort of criterion. After all, most seaside courses are not links. However, without a maritime location, the desired climate, terrain, soil, and grasses for links golf are extremely difficult to achieve. Aside from that, when a course is well removed from the sea—when the ocean’s presence cannot be seen, heard, smelled, or sensed in some tangible way–the authentic atmosphere of links golf simply does not exist. To mention Sand Hills again, this magnificent Nebraskan course looks and plays more like a links than some of those on our list. However, it is not, cannot be, and never will be a genuine links because it is several hundred miles from the nearest sea. To call it a links would be disrespectful to the 246 courses that truly are. (Peper 19)

To arbitrarily nitpicky:

A particularly thorny decision was Chambers Bay, the course scheduled to host the 2015 U.S. Open. Although totally manufactured, it meets all the playing conditions of a links—right down to the fescue fairways and greens. However, its site, on the shore of Washington’s Puget Sound, is nearly one hundred miles from the Pacific Ocean, so we excluded it from our list. (Peper 19)

My point here is not to belittle the authors here over the peculiarities of how they decided to square this circle. Instead, it is to point out the ridiculousness of the authoritative redundancy of calling something a true thing, simply by drawing their own arbitrary lines. And with that, giving people a “definitive” list that is somewhat challenged by the authors themselves. No true Scotsman, indeed!

I would obviously have to do a non-trivial amount of research to identify exactly which beaches are influenced by the Tay and Eden, not to mention the Swilcan Burn, Kindness Burn, or Kenly Water. Different coastal patterns move sand in different directions. The point is that the linksland created by the sources should share extremely similar flora and fauna, and should share similar (if not nearly identical) dune features because of the proximity of wind patterns.

On a personal note, I grew up in Austin, and would play Roy Kizer GC before living in Scotland briefly. They call it a “links-style” course, and I thought it was a links style. I know now, however, that it very much does not play like a links course. Even ignoring the pedantic complaints many about things like soil and turf, the trees along the edges of the course block the wind and the water hazards play a very prominent role throughout the round. It doesn’t even have the characteristics of a links tied in with the Texas landscape. So, I understand the value of protecting the term.

Look, I don’t know anything about grazing sheep, but from what I gather, the lowest grazing height sheep should be grazing to is about 3cm (which I gather from this sward stick video and PDF), whereas the USGA suggests fairways be anywhere between 0.9cm and 1.3cm. If this intuition is idiotic and wrong, please kindly point this out to me if you have the time.

I wish I had a lot more evidence to demonstrate this, because it seems like common knowledge, but the best I can do with launch monitor data is persimmons. Obviously using a launch monitor trained on modern clubs should not be blindly trusted when using nonstandard equipment:

Daniel Wood Golf. “Ping G25 Driver v Ping Karsten Zing Driver (old v new technology).” Daniel Wood Golf, YouTube, February 10, 2015. Accessed February 5, 2025.

Ironically, another video shows doing the same experiments with 7 or 8 iron equivalents suggests very similar ball flight and launch angles with that amount of loft. Again, it think it’s dubious as to whether launch monitor data can be used with nonstandard equipment:

Steve Johnston Golf. “Hickory on Trackman.” Steve Johnston Golf, Youtube, May 11, 2020. Accessed February 5, 2025.

Ebert, Martin, and Tom Mackenzie. “All links bunkers need not be revetted!” Golf Course Architecture, Tudor Rose, 5 June 2018. Accessed 3 February 2025.

Here, I’m open to objections from others. If I’ve missed something about the essential qualities of links golf, then it might hurt my argument.

Hunter, Robert. The Links. Coventry House Publishing, 2018. Page xvii.

Hunter, page xxi.

Companies like Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat often use vague terms like “meat,” “burger,” or “nuggets” because those are not specific enough to be essentially associated with beef or poultry. Soundalikes are also used for Parmigiano Reggiano, like “Parmesan” or “Parmezan.”

Austin 43

Here, an appellation is a formal definition, where the instances that qualify follow deductively. This is in contrast to an informal term like “links” where instances follow inductively, hence creating a significant and necessary lack of precision. This result is the problem of induction.