Visualizing Risk & Reward On the Golf Course

Using Reducibility with Backward and Forward Propagation to Create Clear Illustrations of Course Design

For some, understanding risk and reward trade-offs while playing golf is second nature. For others, it can be challenging. These concepts are much more intuitive when they are clearly illustrated. Borrowing some principles from mathematics, reducibility and both backward and forward propagation, we can visualize strategy in a way that makes it immediately obvious. Strategy in golf might feel obvious to some, but explicitly illustrating each aspect to strategy can show unexpected paths to the green.

1: Reducibility

For our purposes here, we need to use a principle of reducibility. That will be, that we can view a par 4 hole, as effectively two par 3s. Not all golf holes fall into this classification, immediately we should view drivable par 4s, and short par 5s, as not falling under this rubric. However, at least for those holes that play in regulation, we can use this reducibility principle to easily analyze exceptional golf holes, while illustrating why they are so impressive.

Under this analysis, every hole will be reduced to a series of par 3s. First, let’s start with par 3s in general. We have a tee shot into the green, if successful we have an approach putt, and a finishing putt. While every par 3 hole is different. Generally speaking, we should expect the one shot to the green, and two putts. For an example, let’s look at the Postage Stamp at Royal Troon, #8 Old Course:

The hole is straight forward. It’s a short, downhill par 3. We are rewarded for accuracy, and penalized heavily for poor shots. The safest place to play is often far from the pin, but it’s a very small green and there are always trade-offs.

How is a par 4 different in kind? Obviously, we have a tee shot to the fairway, there is more choice in where to play. However, we can reduce the par 4 into two par 3s simply by viewing fairway landing areas as another green. Here, the different teeing areas for a par 3 mimic the better and worse landing areas of a green. Many strategic players do this instinctively. For example, on a par 4, if there are bunkers short right of the green, play the tee shot to the left side of the fairway to take them out of play. This strategy will give you more room into the green. It’s all pretty straight-forward.

Here, I will illustrate the landing zones on a fairway. Effectively, it creates a par 3 to the green, but instead of having discrete tee boxes for different skill levels (blue tees, white tees, red tees), we have a continuous tee box. The colors blend together, with easier and more difficult shots depending on where you land. An aggressive shot could make the following “par 3” easier, while a conservative tee shot will make the following “par 3” more challenging. Here, I imagine a modified version of #8 at Troon, but as a par 4. We have effectively the same hole only after the first shot, and I’ve done my best to keep the tee box colors consistent:

The playable landing area here has some areas that are better than others. The more risk the player takes to get to the yellow area, the more they are rewarded, but at potential cost. We will examine this risk-reward relationship in the next section. Here, just imagine this landing area as a green with a pin in the center of the yellow area. If that landing area acts as a green, we have a fairly realistic par 3. Thus, we play from one par 3 to another par 3. Many types of holes play this way, this is our reducibility principle.

2. Backward Propagation

Backward propagation is the idea of starting at a result, and moving backward through the problem, to the beginning, to find a path of least resistance. This idea, applied to course design, is effective in analyzing reducible holes, like the one above. This type of thinking is often the same intuitive strategy some golfers use when playing. E.g., start at the hole position on a green, find an ideal area to putt from and move backwards to the tee box choosing the best shots.

We’d all like to hit the ball straight to a target on any shot, but assuming we will miss, what’s the best area to miss. Obviously this won’t be one point, but more of a gradient, like in the landing area above. We have a “best miss” area, now we must look at the risk associated with this area. Here, for the sake of simplicity, I’ll generally use a simple risk gradient of our previous landing area1. The following illustration shows the risk gradient of the tee shot on our fictional par 4 Postage Stamp hole. The darker red represents higher risk associated with landing locations.

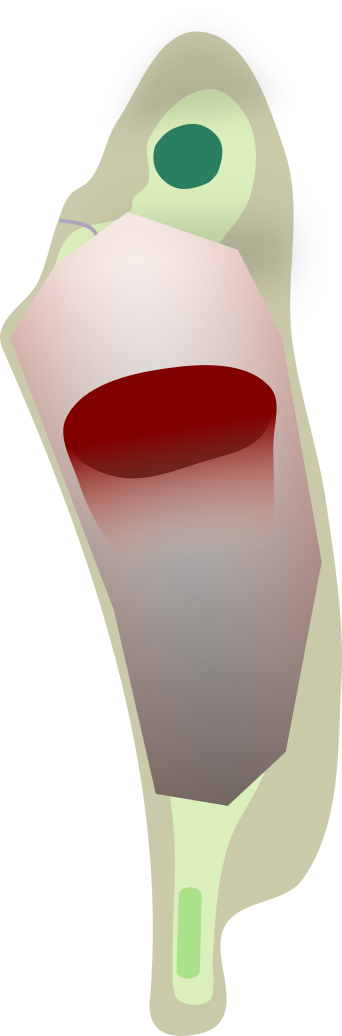

Now that we have a risk gradient, we can combine it with our original reward gradient. We combine the two to find our ideal landing location. Here, the black areas represent areas with little reward, red represents rewarding area with the highest risk, and the lighter pink/gray areas represent the ideal landing locations with a good risk-reward trade-offs:

Here we have our ideal tee shot given our standard error off the tee. This should be the best realistic strategy to get a decent shot into the green.

We can repeat this process until we are back at the tee. The process ends at the tee, because it’s effectively a single point. We’ve established our best risk-adjusted landing areas throughout the entire hole. If we’ve worked through this process, we can take our tee shot with confidence.

3: Forward Propagation & Strategic Design

Once we have our backward propagation mapping, course design for this type of player becomes much more straightforward. We can then move forward through the hole, adding hazards in areas if we want to manipulate these risk-reward gradients. As long as we move forward as we manipulate risks, the next-ideal landing location should not change.

Suppose we wanted this landing area to be more exciting. If we want to push players toward the forward tier (the original yellow area) of the landing area, we could simply add a bunker on the left side. By adding this bunker, we do make the hole much more difficult, but we also move much of the ideal landing area forward:

By adding and removing hazards in this way, the designer can manipulate the line of play, and the risk players will take, in ways that are much more nuanced than just adding length. Simply adding length can be problematic. It always punishes older players and players don’t have the same strength. This process can make it fairly straight-forward to add risk-balanced rewards to longer players, while leaving the shorter, but still accurate player, effectively on reasonably equal footing.

4. Excellent Design Case Study: #1 at Lincoln Park GC, San Francisco, California

The penal, heroic, and strategic schools: how risk-reward gradients give us another tool for understanding why a hole can be rewarding for everyone.

Here, I propose the use of these gradients to illustrate the subtleties of great course design, and how our typical three schools: Penal, Strategic, and Heroic, all interact with each other. Let’s look at #1 at Lincoln Park GC, through a few lenses. The hole is 316 yards, sharply uphill right before the green, so reaching the green should not be possible for most. Before we look at the actual hole, let's look at different versions of how it could have been through the lenses of different design schools. Firstly, let’s visualize a completely stripped down version of the hole, with no trees, and no out-of-bounds:

This is a fairly wide open hole, without severe penalty anywhere. This hole favors distance off the tee more than anything else, but not really by much. Any player can take any approach they choose here.

First let’s design the hole from the penal school perspective. It’s often the type of design when you’re gritting your teeth and thinking, “don’t miss.” It can also be the type of design when a bunker makes you wonder why on earth it is there. Here, we add two large bunkers along the sides of the fairway. Playing a shot too far right, or too long and left, will be punished heavily. These are the standard misses for the right handed golfer, so the hole here tests only a correctly played shot.

This school is defined by emphasizing shot accuracy. The risks in play should be obvious, so the player isn’t fooled. There is hardly a strategy here in playing to the left side, rather than to the center of the fairway. Instead, the risks are defined and contained only within the bunkers themselves. No type of player gains an advantage except through precision in shot placement.

Now let’s change the hole to illustrate the heroic school. The heroic school is defined by discrete challenges. That is to say, this school uses pass/fail hazards, where you choose “go for it,” and if you do, there are very specific risks and rewards. We place a large forced carry into the center of the fairway, in this case a fairway bunker:

Looking at the risk-reward mapping, we see that distance dominates the reward characteristic of this hole. There is a bit of interesting risk-reward happening in front of the bunker, but again, anyone seeing this payoff structure can clearly see being long off the tee is paramount.

Let’s look at the results if we add a continuous hazard, instead of a discrete hazard. Continuous hazards are hazards that, the closer you get to them, the more risk you take, but there is no need to “go for it” over just choosing the amount of risk you want to take. Here our continuous hazard will be trees:

The image here is a quintessential example of the strategic school. You can see how the trees dramatically affect the reward for certain landing locations far more than the direct risks involved in making said shot. This rewards the player who thinks about their shot, while the player who simply aims for the middle of the fairway will find themself in trouble simply because they didn’t examine the benefits of position.

In this example distance is rewarded, but shot accuracy is far and away the most important aspect of the hole. Any player who isn’t long off the tee, can still attack the hole to the best of their ability. Their good play will still be rewarded. Still, here, the long hitter can simply aim left and swing away. It’s not very interesting for them. If we want to limit the effectiveness of certain skills, we can add further hazards.

Finally, here, we get to the actual hole. It has out-of-bounds along the left side. This is another discrete hazard, but it adds continuous risk. It allows the player to gain as much potential reward from moving the ball as far left as they feel comfortable with:

The effect here creates an incredibly compelling tee shot akin to the type of risk-reward that created the strategic school at the 4th hole at Woking. The greatest area of reward is mapped to the greatest area of risk, while at the same time, players can attack the hole at their own level of risk tolerance. Better players will be rewarded, but not simply because they can hit the ball farther. In fact, due to the inherent riskiness of longer shots, the maximized risk-reward payoff area actually narrows as distance is added until opening back up again. Shot making still matters here.

5. Conclusion

This type of hole, with this risk-reward mapping, illustrates complex strategy. The penal school is typically limited to the risk sections of the mapping, but the heroic school adds clear rewards to taking specific risks. The strategic school can be viewed as weighing reward outcomes, or for weighing both risk and reward outcomes put together. However, the strategic school seems generally focused on optionality, instead of quantifying and measuring specific risks and rewards. The interplay between the reward and risk seems to be generally overlooked or assumed as obvious, when they are separate entities shaping the course.

Shot risk cannot be discrete, because of the inherent potential error in every shot. Obviously, this dispersion will be dependent on skill level and type of shot, but there will always be danger inherent. Positional rewards, however, can be discrete. One could have a perfectly playable shot a foot from a bunker, with the exact line of positional benefit being the bunker. Positional rewards can also be continuous, such as the distance from a tree that requires more shot shape as one moves closer.

Here, I see a new way to describe the interplay between risks and rewards on the course:

Shot risk with no positional reward, e.g., a pot bunker on the side of a fairway: penal risk, typical of freeway-type hole designs.

Shot risk with discrete positional rewards, e.g., risky forced carry: heroic risks, typical of the heroic school of golf.

Shot risk with continuous positional rewards, e.g., a fairway bunker at turn of a dogleg: strategic risks, common in the strategic school of design.

Continuous positional rewards with no shot risk, e.g., seeing that a tree will make the next shot more challenging from one side of the fairway: this is strategic forethought, it should be employed often in course design to reward smart play without punishing beginners.

Discrete positional rewards with no shot risk. It’s hard to think of an obvious case of this short of hitting a shot over a strong drop off with tons of roll out: Swing away/grip it and rip it. These holes tend to be fun. They can be a good break after a series of extremely penal holes.

Armchair course designers can benefit from describing these trade-offs explicitly. Creating language for each type of trade-off can benefit strategic thinking on the course. While shot risk can intimidate people on the tee, potential positional benefits tend to only engage thoughtful players. I plan to use this risk-reward methodology in these essays when examining specific golf holes in detail.

I write here to promote golfcourse.wiki, a site dedicating to mapping and promoting smaller public and muni courses, and sharing local advice for free. If you want to share your favorite course, sign up and start editing today. If you liked this article, join the discussion on the golf subreddit.

This can be extremely complex, considering that any club can technically be used, thus the risks associated with any landing area will be very diverse. If one were actually designing a course or doing an analysis through this method, multiple iterations of this process should be done to examine the hole with different approach techniques to each landing area. Beyond this, analysis of different players, each using many different clubs should be done. If done programmatically, even multidimensional analysis like this should be very straight-forward.