Many poor golf courses are made in a futile attempt to eliminate the element of luck. You can no more eliminate luck in golf than in cricket, and in neither case is it possible to punish every bad shot. If you succeeded you would only make both games uninteresting.

―Alister MacKenzie1

A good kick, a poorly timed gust of wind, playing out of a divot, hitting a good miss: good and bad, luck shows itself in every round of golf. Most see luck and skill acting in opposition to each other and think great courses should do what they can to reduce the amount of luck involved. Here, I want to argue that luck and skill are actually two different aspects of a game. Increasing the amount of opportunity for luck on the course, when appropriate, will improve players’ experience without robbing higher skilled folks of winning. Luck and skill can work with each other to create excitement and drama. Many of the most well regarded holes in golf, when played well, will feature a lot of luck and a lot of skill.

Because this article relies so much on others’ work on the subject, I want to give full credit to those authors now. Richard Garfield and Skaff Elias’s lectures on luck in games is the primary source, but also Ben Brode’s GDC lecture on Marvel Snap and Game Maker's Toolkit video on types of randomness.234567 This article simply extends these theories of luck in games to the game of golf.

Understanding Luck and Skill

What do we mean by luck and skill? In golf, the winner is determined by who gets the ball in the hole in the fewest strokes. There are skills that one can acquire to facilitate getting the ball in the hole with the fewest strokes, but those alone aren’t necessarily skill at golf, itself.8

One way we can show how luck isn’t in opposition to skill is through toy games. Toy games are simple games used only to demonstrate a concept. They are not meant to be serious, and are not supposed to be fun, but they can show us how luck and skill are not exactly in opposition.

In his lectures Richard Garfield refers to the toy game “rando-chess” to demonstrate how luck and skill are not linked. Here, I’ll use the same concept illustrated as “rando-golf.”9 “Rando-golf” is effectively a game of golf, but at the end of the game a dice is rolled and if the roll is a one, the person with the worst score wins instead of the best score. The point is that the amount of skill in the game obviously remains unchanged, and skill still gives the player a huge advantage, winning five-in-six times. It’s just that we’ve added a huge amount of luck to the game by leaving one-in-six games to pure chance.

Another toy game that can illustrate that luck and skill aren’t opposites, we can call “drain-golf.” Drain-golf is a game where players putt the ball into a large drain that counts as the hole. Any shot that fails to reach the drain (for any reason) must be retaken without penalty until the ball reaches the drain. In this game every player always gets a hole-in-one. There is no skill or luck here, yet we can still add luck to the game. How? Well, imagine rando-drain-golf, which is just drain-golf where the winner of a tie is determined by a coin flip. Here, we take a toy game with no skill and no luck, and add an element making the game completely determined by luck.

Luck and Skill in Games

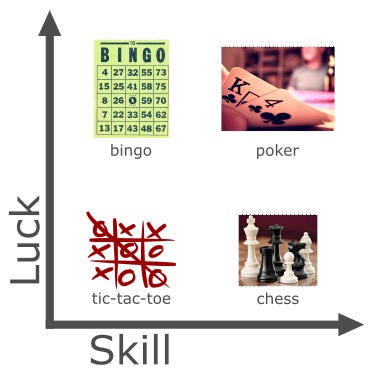

We can illustrate how luck and skill are two different variables in games by plotting them against each other and looking at a few common games:

Here we see how these games diverge in their use of luck and skill.

Low Luck & Low Skill: Tic-tac-toe is a perfect information game with nothing left to chance (low luck), and is so easy that a novice will soon learn how to solve the game (low skill).

Low Luck & High Skill: Chess is also a perfect information game with nothing left to chance, however, unlike tic-tac-toe, the game is the archetype of the skill in strategy and forethought (low luck, high skill).

High Luck & High Skill: Poker is a game where there is luck involved in every deal of every hand, but statistical strategies allow players to maximize their chances against each other. The most skilled players can’t win every hand with a bad run of cards, but they should still come out on top in the long run (high luck, high skill).

High Luck & Low Skill: Bingo requires no strategy of any kind (no skill), and is completely dependent on the random draw of numbers (high luck).

This illustrates the concept for tabletop games, but how does it translate to golf? Skill in golf is about being able to put the ball where you want it, so why would luck be involved? Well, yes, golf is a skill game, but players have limitations, and where these limitations start coming into play, luck starts to play a big role.

Types of Luck in Golf

Luck in games is effectively about randomness, or unpredictable events. In golf, one of the most obvious cases of randomness impacting the outcome of a hole is when the ball ends up in a divot instead of perfect turf just inches away, or when the ball ends up in a footprint someone left in a bunker instead of raked sand. However, randomness in golf might present itself in less obvious ways, for example, in players’ physical limitations. A highly skilled player may hone their dispersion pattern to a five-foot circle, but there are physical limitations to how tight that dispersion pattern can get, and in what conditions. Again, the results here aren’t completely random, but for all practical purposes randomness exists within certain parameters.10 The two main types of randomness are output randomness and input randomness.

Output Randomness

Output randomness is randomness that takes place after an action has happened. If a shot were to, say, be picked up by a bird, that happens after the player makes their shot, so they have effectively no control over the outcome.

Most output randomness we notice will be an unpredictable wind gust or bouncing off a sprinkler head. Once the ball is in the air, players can’t really control how the wind, or a curious bird, might affect the ball. On a blustery day, if one player hits the exact same shot twice, it can end up in two very different places. We can think about where the ball lands in a player's dispersion pattern as a type of output randomness, because there is a limit to the extent that it’s controllable.

Some types of output randomness include:

landing location within a dispersion pattern,

wind gusts after a shot has been taken,

ball ending up in a divot or footprint,

ball bouncing off a sprinkler head or a cart path,

ball hitting a tree and deflecting back into the fairway or deeper into the woods.

Input Randomness

Input randomness, on the other hand, is the randomness that happens before the player makes their shot decision. Input randomness is not something that players can control, but can strategically react to. The most obvious example of this is hole location. Depending on the hole location, players may choose a completely different strategy. In the illustration below, on the left, if a green has a high risk pin position (Sunday pin), the player might just play to the safest part of the green and two putt. However, if the pin is in a welcoming position (Friday pin), players may choose to attack the pin instead of aiming for the center of the green. The Sunday pin gives the player with a very tight dispersion pattern a large advantage, while the Friday pin is much more friendly to a greater number of players. The player isn’t in control of where the hole location is on each day, but they will know where it is before they have to play.

The illustration on the right illustrates how the input randomness on a double plateau green can influence how players approach the entire hole.11 When the hole location is on the left side of the green, the ideal play off the tee is to the right side of the fairway. When the hole location is in the back-right of the green, the ideal play is to the left side of the fairway. The line a player takes here will probably depend on where the flag is. These locations aren’t under the control of the player, so it’s easy to see how this type of input randomness has a lot of potential to affect who wins.

Types of input randomness include:

hole location, especially on double plateau greens where hole location affects the best way to play the hole;

tee locations;

wind speeds (on a day-to-day basis);

turf firmness (on a day-to-day basis);

green speeds (on a day-to-day basis).

The result of the previous shot can be thought of as a form of input randomness for the next shot.

A bit of input randomness is common on golf courses, but Ballyneal Golf Club takes input randomness far beyond most courses. At Ballyneal, there are no set tee boxes, and it is customary that the tee location is simply chosen by whoever won the previous hole.12 Because of this, the course doesn’t have a course rating, but it adds a huge amount of variety to how the course plays between each round. An interesting feature for less serious competition could be allowing the loser of the previous hole to choose the next tees, which would create a form of catch up balancing system.

George Thomas was known for a similar feature of his courses. He would design courses that played in different ways, on different days, sometimes even changing the par value of the course.1314 In this way, if players do not know which version of the course they are playing before the round, this will create an incredible amount of input randomness. Allowing the winner/loser of the previous hole to choose which version of the next hole to play would be a huge extension of the type of input randomness at Ballyneal. The impacts on strategy are immense.

Information Horizon

Finally, another aspect outside of players’ control is the information horizon. Information horizons are where the player has no sensory clues as to conditions beyond a certain point. Blind, or semi-blind shots are a type of designed information horizon. Before rangefinders became common, uniform flags (instead of blue, white, or red to mark depth) acted as another form of information horizon, forcing players to guess at the hole location. Many architects intentionally limit players’ view of the playing surfaces exactly to create uncertainty and add risk to shots.

Luck & Skill Quadrants in Golf

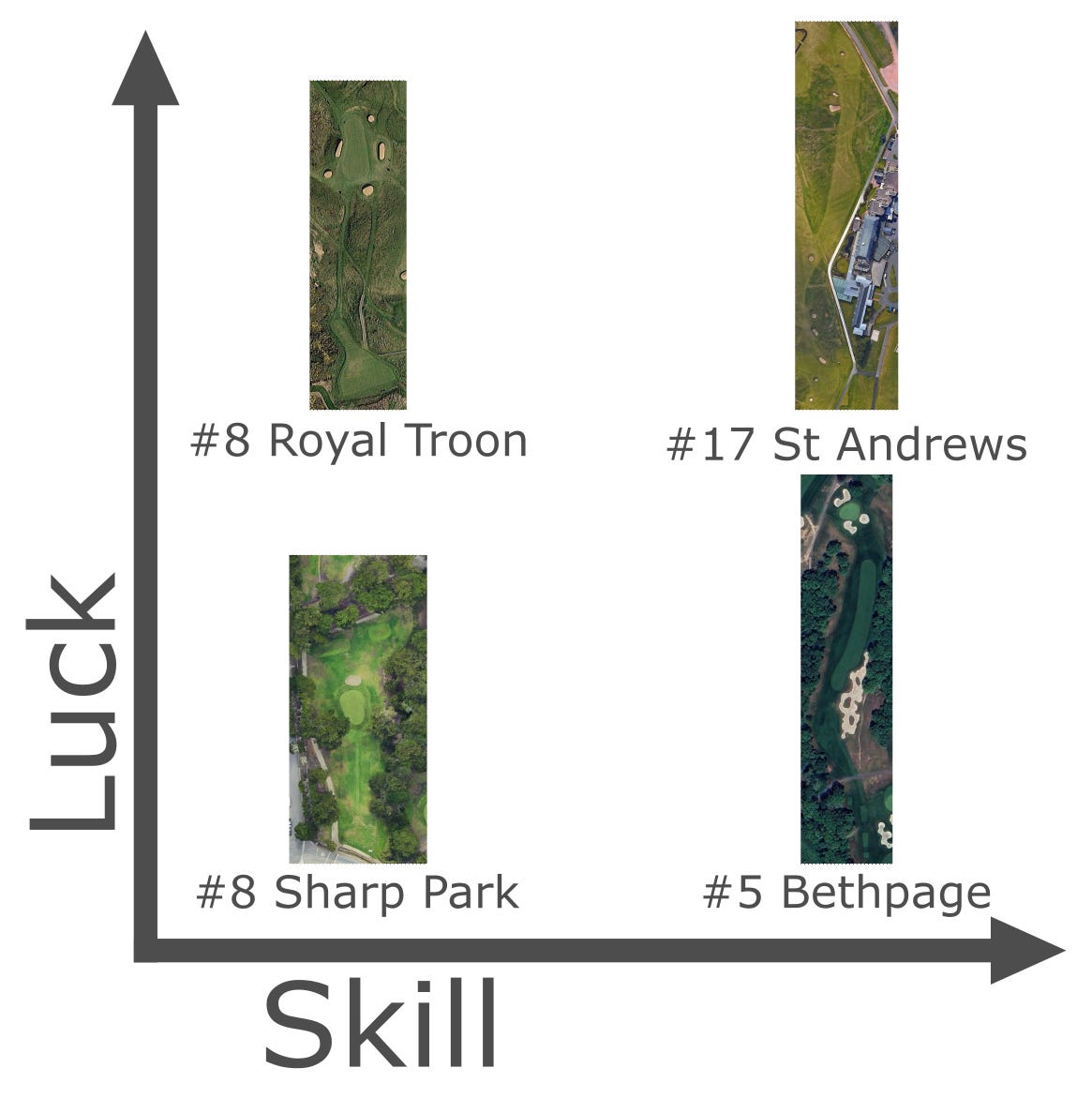

With this understanding about types of luck and how architects might implement them, we can look at how different golf holes map to our luck and skill quadrants:

Low Luck & Low Skill: #8, Hollins, Sharp Park

Sharp Park’s eighth hole is about as easy as they come. A 99-yard hole from the back tees, no more than a gentle wedge to the generous green sloping back-to-front. The trees beyond the green block any ocean wind that could make this hole challenging. The single bunker beyond the green is effectively out of play, simply protecting other players on adjacent tees from an errant shot that could kick towards them. This hole is a realistic par even for the highest handicapper.

Low Luck & High Skill: #5 Bethpage Black

The fifth at Bethpage State Park’s Black course is an absolute test of mastery of the golf swing. At 478 yards from the back tees, this par 4 requires both excessive power and absolute precision. Simply reaching the fairway is a test. Players will need to hit a 235-yard drive, with a 230-yard carry, to clear the shortest distance across the bunker. However, conservative play leaves nearly no chance at the green. Any short position leaves trees blocking direct access to the green. To even flirt with a look at the green, players will need a 270-yard drive, with a 260-yard carry. This shot is extremely difficult to pull off without even considering the penal consequences of the bunker or trees.

The approach to the elevated green is no easier. An uphill shot that requires players to fly two front bunkers while holding the green with a punishing bunker directly behind the green that will catch anything that runs through. In a sense, this penal hole allows players to take as much risk as they like, but more than anything, it demands distance and accuracy, while punishing any mistake.

High Luck & High Skill: #17, Road, St Andrews

The Road hole is one of the most challenging holes in golf and is a notorious card wrecker. At 455 yards, players will need two well struck shots just to reach the green. However, the complication here is that the first shot is blind, typically plays into high winds, and risks out-of-bounds just a few feet from the fairway. Assuming the player has a decent drive, the long approach shot plays to a narrow green that drains into a fierce bunker on the left side. Any approach that goes right or long must be played from the road itself, or worse, against the adjacent stone wall. Even a small, unpredictable miscalculation on this hole could add multiple strokes to the player’s final score. Any attempt to birdie the hole will take incredible skill, and even then, one unlucky bounce could mean the difference between birdie and double-bogey, or worse.

High Luck & Low Skill: #8, The Postage Stamp, Royal Troon

At only 123 yards from the back tees, the Postage Stamp should be hardly more challenging than #8 at Sharp Park if the player reaches the green. The only difference between the two is the strong winds and the severe penal architecture that will turn even the slightest error into a complete disaster. Any recovery from the bunkers around the green will be nearly as challenging as reaching the green itself. Since the tee shot isn’t particularly difficult, much of the result can depend on how the wind moves the ball in the air. Since this can leave things outside the player’s control, this hole is likely the only one of these four holes where a mid-handicapper could frequently beat a professional’s score.

But Why Add Luck?

It is an important thing in golf to make holes look much more difficult than they really are. People get more pleasure in doing a hole which looks almost impossible, and yet is not so difficult as it appears.

In this connection it may be pointed out that rough grass is of little interest as a hazard. It is frequently much more difficult than a fearsome-looking bunker… it causes considerable annoyance in lost balls, and no one ever gets the same thrills in driving over a stretch of rough as over a fearsome-looking bunker, which in reality may not be so severe.

―Alister MacKenzie15

People tend to enjoy randomness when it helps them. Not all random events are zero-sum, and architects may add subtle design elements to favor good luck over bad. A surprising kick on a concave fairway will tend to help players, whereas the same kick on a convex fairway will likely have them moaning and calling the fairness police. If you pay attention, you may start to notice that some forced carry bunkers are actually (intentionally) pretty easy to play out of. Keep an eye out for friendly recovery zones that were probably designed to give the player a chance at saving par after they failed their attempt at a risky shot earlier.

The design left punishes a failed carry, while the design right offers a chance to save par.

Playing on a low-luck, penal course, good shots are rewarded and bad shots are punished, and that can be very frustrating to those who don’t have a perfect swing. Imperfect players likely don’t have the time or desire to regularly practice at the range, but still want to have fun playing against their friends. A bit of luck can also add drama to an otherwise easy hole. When an architect only has a hundred yards to work with, using high risk elements, like wind, can make a trivial hole exciting.

Adding elements of luck forces risk management. No matter the skill level, designers can create features that make players take risks and play the odds instead of just playing to their strengths. These wild features tend to be most prominent on match play courses, where the prospect of carding double digits is irrelevant to the overall game.

Why Reduce Luck?

Players who invest time and energy into their game would obviously prefer courses that test more of the skills they try to acquire. Different courses (or at least different tee boxes) can and should serve different types of players. Courses that are low luck and low skill are probably best to serve beginners’ preferences, while courses that are low luck and high skill are probably best to serve professionals.

Also, most people see randomness that hurts them as incredibly frustrating. Front and center is the issue of ending up in a divot or in a footprint in a bunker. There aren’t any easy ways to ensure etiquette like replacing divots and raking bunkers are respected, though some designers help divots heal by building reversible courses, like the Loop.16 A reversible course with distinct landing zones will give each section of fairway a full day to rest and recover while the course is being played in the opposite direction.

Contradictions

These general rules, of course, will be met with eye-rolls from many architecture enthusiasts. People who can identify designs that make everything helpful won’t be as excited to play a course that turns out to be a paper tiger. To explain this contradiction, we can look to priming and reputation.

First, frustrating aspects of courses can be entertaining if they aren’t overwhelming. This is especially true if these features are anticipated. A course’s reputation matters; it sets expectations. Holes that have a reputation for leaving a lot to chance can become iconic. A bad result can be waived away by bad luck, and a good result can be cherished. Heathery (In) at the Old Course is renowned for its completely hidden fairway bunkers, but there probably isn’t a person who has played there who wasn’t aware of them. The Postage Stamp’s near-inescapable coffin bunker leaves players feeling they’ve accomplished something simply by not landing in it. And 17th at TPC Sawgrass is loved exactly because it’s so difficult, not in spite of it.

How Different Types of Players Approach Luck

Unlike beginners and professionals, golf enthusiasts and casual golfers would probably be best served by courses incorporating both a bit of luck (making the game exciting), and elements that reward the players’ skills. How we decide our favorite golf courses, though, depends on what our value propositions are. Richard Garfield talks about four player types, and different courses will appeal to each of them.17

“Innovators” like to try new things and explore all the strategies, and try different ways to approach each hole.18 They definitely subscribe to the strategic school of course architecture, and will likely be open to higher luck courses.

“Honers” are folks who like improving their existing skills. They are the people with a TrackMan at home and are at the range at least a couple times a week. They will probably prefer lower luck courses, and are usually fans of penal architecture and the challenging shots presented by heroic architecture that really reward skill when the stakes are high.19

“Watchers” just like to see exciting things happen. They are risk-takers who will take every chance to drive the green. They’re also the type of golf fans who love seeing professional players pushed to the limit. High luck courses and heroic architecture are fantastic for these folks, because they usually care more about exciting outcomes than their score at the end of the round.

Finally, “flow seekers” like to play just for the fun of it. They aren’t entirely concerned about honing their skills, but they like the game’s process and find it relaxing. The type of course for these players is probably less important, so long as they can get in the zone. The only thing that these folks might not prefer is jarring, gimmicky holes.

Each of these player types will have different opinions about how luck should affect their game. They will probably disagree in how they view different courses and designers. It’s useful to understand that the “best” course for a honer-type player will most likely not even be considered a good course by an innovator. We can learn a lot about what type of player we are just from thinking about which courses we like.

There will always be folks who see the game of golf as simply an execution of the standard golf swing. When I hear players calling for narrower fairways, longer rough, and a removal of fairway bunkers, I understand exactly what type of player they probably are, but I feel like a lot is lost when we start trying to remove luck from the game. Much like poker, golf is a game that has many rounds, and on a high-luck course, we should still expect skill to be the deciding factor in the long run.

But by allowing a bit of luck in the game, we allow for more excitement for more players in the short run. Over the course of 18 holes, we should expect the best players to show their skill through not just their standard shots, but also their recoveries from bad luck. Embrace a bit of luck on the course, and you might find yourself playing a more dramatic game, and having a bit more fun.

MacKenzie, Alister. Golf Architecture: Economy in Course Construction and Green-Keeping. Coventry House Publishing, 2019, p. 20.

Garfield, Richard. “Luck in Games.” YouTube, 14 September 2013,

. Accessed 29 July 2023.

Garfield, Richard. “Dr. Richard Garfield on "Luck Versus Skill."” YouTube, Magic TV, 10 July 2012,

. Accessed 29 July 2023.

Brode, Ben. “Designing 'MARVEL SNAP.'” YouTube, GDC, 3 May 2023,

. Accessed 29 July 2023.

Game Maker's Toolkit. “The Two Types of Random in Game Design.” YouTube, 14 January 2020,

. Accessed 29 July 2023.

Elias, Skaff. “Luck and Skill in Games.” YouTube, GDC, 20 February 2017,

. Accessed 30 July 2023.

Elias, George Skaff, et al. Characteristics of Games. MIT Press, 2020.

So, let’s look at different skills individually. Long, straight drives will certainly facilitate improving the odds of winning golf. Good course management will also improve the odds. Shot shaping, short game, putting, etc., will also contribute, but none of these skills alone will measure “golf skill” as different courses call for different attributes.

There are plenty of different skill rating systems, with the Elo system as arguably the most prevalent. However, all these systems rank players generally to predict the probability of outcomes of games. This is important when we talk about games like rando-golf (explained later in the text) because rando-golf will still rank players in the same order after a long enough period, because the random outcomes only affect a minority of the results.

Contests, if they are to be sensible at all, must allow for some potential indeterminacy in result. This concept is obviously very philosophically challenging, but without it, contests would be wholly uninteresting. The literature refers to the contest of “who’s taller” as an example of a contest with a predetermined outcome that is uninteresting as it is nonsensical (Skaff 2017 15:58-16:23).

The Fried Egg. “C.B. Macdonald's Ideal Holes: The Double Plateau Template.” YouTube, 13 February 2020,

. Accessed 4 August 2023.

Hafer, Christian. “Field guide: This Colorado course is skyrocketing up the Top 100 in the World ranking.” Golf Magazine, 11 June 2020, https://golf.com/travel/ballyneal-skyrocketing-top-100-world-ranking/. Accessed 4 August 2023.

Wikipedia. “George C. Thomas Jr.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_C._Thomas_Jr. Accessed 13 August 2023.

Passov, Joe. “Captain Fantastic: Architect George C. Thomas, Jr.” FORE Magazine, 1 August 2018, http://www.foremagazine.com/profiles/captain-fantastic-architect-george-c-thomas-jr/. Accessed 13 August 2023.

MacKenzie 22

O'Neill, Dan. “Reversible golf courses gain in U.S. popularity.” Sports Illustrated, 27 April 2020, https://www.si.com/golf/travel/feature-2020-04-27-reversible-golf-courses-in-the-united-states. Accessed 8 August 2023.

Garfield 2013 15:35-17:50. Garfield 2012 33:22-35:56.

Fried Egg Golf. “Golf Course Architecture 101: Strategy.” YouTube, 2 November 2018,

. Accessed 14 August 2023.

Fried Egg Golf, and Tom Doak. “The Different Schools of Golf Design.” YouTube, 8 November 2018,

. Accessed 14 August 2023.