Dunaverty Golf Club

Perhaps the ultimate third place in golf

While my trip to Scotland this year was for the Buda event, there were two golf courses I went out of my way for. I wanted to try to get down to Kintyre specifically to visit Dunaverty Golf Club. As I’ve stated before in this series, I’m a fan of Jim Hartsell’s writing on golf. In his books and interviews, he talks about Dunaverty at length (he’s a member). As a fan, I think I’d be doing myself a disservice if I didn’t try and see what he’s on about with a relatively unknown golf course in an obscure part of Scotland.

Dunaverty is Breathtaking

Dunaverty Rock, the Mull of Kintyre, Sanda and Sheep Islands, and the Antrim coast are all visible as you move through enormous dunes at Dunaverty. After crossing the burn that cuts the course in half, you’ll need to pass between dunes that are easily 20 feet high. The first two-thirds of the course will be some of the most undulating terrain you’ll ever play. The walk above the beaches is incredible, even if the best views mean you’ve hit a poor shot.

You start out heading toward the sea, then you play along the coast through the dunes. Just after you make the turn, you’re taken up to a high point on the course, to look back over everything you’ve played. The photo op is perfect. The view is as exhilarating as the shot back down to the water. Then you head back up the hill inland, where you’ll pop in and out of sight of the coast, until finally you get one last clear look at the 17th green, before turning toward the clubhouse at the end of the round.

Why You Won’t Find It on Any Lists:

I’m a bit shocked that Tom Doak gave Dunaverty a Doak Scale “2” in his Confidential Guide, but I certainly know why many folks don’t rank it higher.1

Length

The fact is that Dunaverty GC is par 66, 4799 yards. That’s well short of the minimum par 70, 6000 yards expected of modern courses. Whether or not these are hard and fast expectations, absent a blustery day, many of the holes are going to be too short to challenge the long hitter. That said, given the location, a blustery day should be expected.

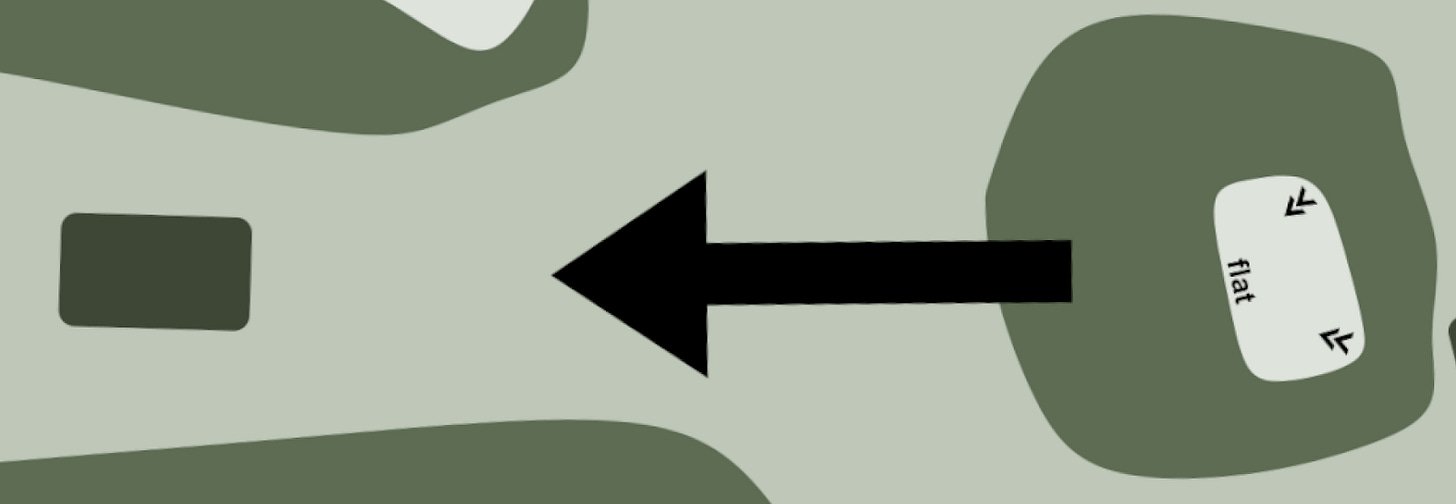

The Quiet Finish

There seems to be a lot of criticism paid to the closing holes (13-18). Some suggest they fail to deliver the same level that the first ten do. While there are scenic views through this section, they are not as intense, and they are definitely not very well framed by comparison. Many of the holes have players looking away from the sea. For those focused on the large contours, the holes along the course’s floodplain may disappoint. The course does not revisit the sea. The volume starts to get turned down, and the round gets more and more quiet, until it fades away back at the clubhouse. I can both see how people feel that the intensity of the links is not there on these holes and agree with the sentiment, but disagree with the premise.

First, I think the 13th and 14th holes are excellent. They are both highly contoured, have remarkable views, and are both strategic. Next, the approach to the 17th is one of the most anticipated shots on the course, even reminiscent of the first hole at the Old Course. Lastly, I’m entirely supportive of a quiet finishing hole. I’m a match-play zealot who thinks the last hole should be a birdie-fest so tight matches are “won with a birdie” and not “lost with a bogey.” So, for me, this leaves holes 15 and 16 and I’ll be honest that – while these are perfectly serviceable golf holes – they aren’t as spectacular as the rest of the course. For folks on a vacation to see only the best and most expensive course in the world, yes, I can see how this might make them balk. For me, it just adds character – a bit of wabi-sabi for a course that’s nearly a century and a half old.

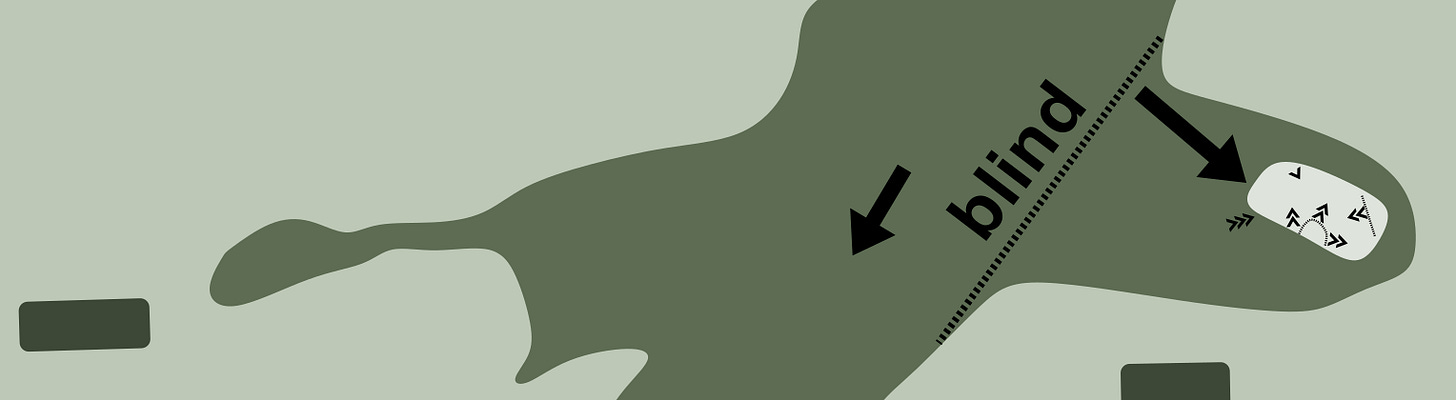

A Distinct Lack of Bunkers

Something players might not notice during their round is that there are not really many bunkers on the course. In fact there are only two, and they are both quite small. The only other notable hazard is a creek that crosses the fairway short of the 17th green. One of the two bunkers is on the seventh hole, where if the player misses short, they will be dragged down into the depths below and end up in this bunker. The other is an unassuming greenside bunker on the 16th hole. And I will admit, the lack of bunkers does seem odd if you notice it.

A Defense of the Bunkerless

Here, I think this lack of bunkers is worthy of discussion. There are some out there who see strategic golf as first and foremost press-your-luck strategies executed against various hazards on the golf course. Here, the lack of bunkering implies the lack of strategic interest. I would push back against this line of thinking. The clear delineation of bunkering gives a guide to the thoughtful player, yes, but the not-so-subtle contouring that one must play around at Dunaverty will create strategic advantages for the local who knows where and how to hit shots in different winds, and where and why the shots will miss safely when they are imperfect.

The Press-Your-Luck Strategy of Bunkering

While I wholeheartedly agree that press-your-luck as a strategic interest is very real, my main concern here is that it is very much not the only form of strategic interest. Bunkering does supply a high penal gradient, onto which a slight misjudgement is punished, which means strategic caution should be employed. The difference of one foot can mean a perfect lie on the fairway versus a miserable pitch from the sand. However, high penal gradients in highly windy courses lend themselves to significantly more luck than many might like. If the course also includes wild contours, the amount of luck involved might be a bit much.

Wind as Exaggeration

I see wind, as a hazard, as woefully underappreciated in modern golf. Where the bunker defines areas of danger on the ground, wind is often much more hazardous even if it’s less obvious. At Dunaverty, misjudging a strong wind on any of the opening 12 holes can easily lead to a lost ball, but another relevant danger is just that players might end up on the wrong side of a dune. And with wind, we may require a knockdown or ballooning shot depending on how these contoured dunes interact with the hole.

Whatever the misjudgement, a headwind or crosswind will exaggerate that miss. Thus, we don’t actually need the sharp gradients of bunkering to capitalize on strategic interest. The ballooning shot in the headwind misses by 50 yards. Having a bunker there to catch it makes little sense as the advantage gained by the careful player will certainly outweigh the half-shot disadvantage that a greenside bunker would have created. The penal gradient of a bunkerless course may seem more subtle, but again, the wind narrows that wider margin for error.

Large Contours as Large Tipping Points

It would be foolish to discuss Dunaverty without mentioning the most enormous, and strategically consequential contours on the course:

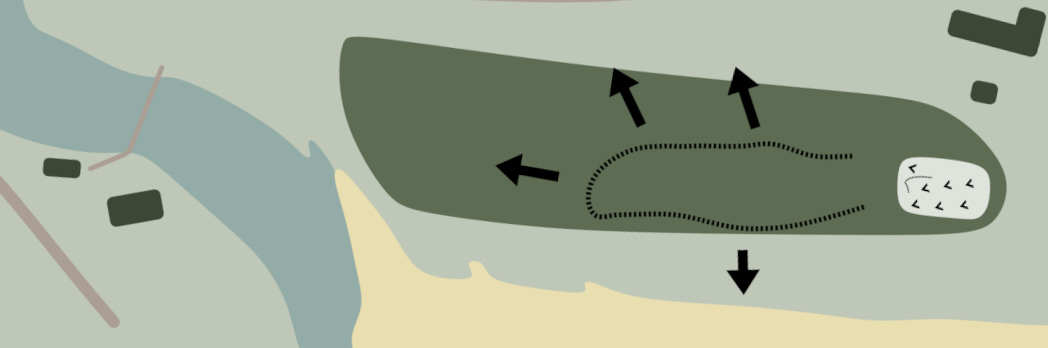

The first obvious example is the fourth hole, where a mound blocks the front end of the green, with a punchbowl beyond it. Here, a player who feeds the ball into the punchbowl will be rewarded. But the player who misjudges the hole short ends up with a blind pitch in. And a player who misses long will likely fly the green completely and end up with a nasty downhill chip. On a still day, there is plenty of room for error here, but the prevailing wind is usually a headwind of some kind.2 This means the biggest unknown on the hole will be distances, with ballooning shots being a real concern.

The fifth hole requires anything less than a perfect tee shot to be moving toward the center of the fairway to hold. Shape a shot into the central fairway contour and you have a chance to hold it and have a decent approach. Anything offline will run into the rough, and the prevailing crosswinds will push the ball left, meaning players trying to hit something straight will need to start their shot toward the beach.

The seventh plays like an Eden hole on steroids. Don’t miss it short! So the safe shot is to miss it long, which leaves a nasty downhill putt that moves right toward the danger.

The ninth hole is surreal. It’s something out of a bizzaro version of golf architecture. The goal is to play over a ridge to a blind punchbowl green. The awkward thing is, though, you could play it just to the ridge, and the ball would run all the way down and onto the green. You could also play to number, hitting it high, with zero reliance on getting a good run out. Either option is an entirely sensible way to play the hole. This type of optionality (which is inherently anti-penal because the hole is easier when you have multiple ways to play it), is still highly strategic. On a windy day, you may hit a knockdown to the ridge and just run it over. One a clear day, you may want to try and get it as close as possible to the number you want to hit. Either way, you’re choosing a viable tactic and trying to execute it well.

The 10th is a second hole with Eden template-like qualities, where you can’t miss short, but missing long leaves a nasty downhill putt toward the danger. Here, again, the volume turned all the way up. The hole might be considered absurd to some, playing straight up hill, except that the architectural principles are right there to see. Miss left if you must, or right if you must, just don’t miss short, and expect a terrifying putt if you are beyond the hole.

The 13th, where the course tends to quiet down, is the last of the contour-focused strategy. There is out-of-bounds all along the right, so the safe play is to the left, however, there are two trenches that meet on the left side, exactly where it is safe to land the ball. So taking the safer path could make reaching the green in two difficult, if not impossible. The canny player who takes on the hazard right, should have a clear shot and a chance to squeeze through a narrow opening to reach the green in two. On this hole, yes, a fairway bunker on the left would provide a more obvious strategic threat, but it’s not necessary. The “valley of sin”-style hazard here provides enough trouble to the scratch player to limit the number of risk-free eagle putts.

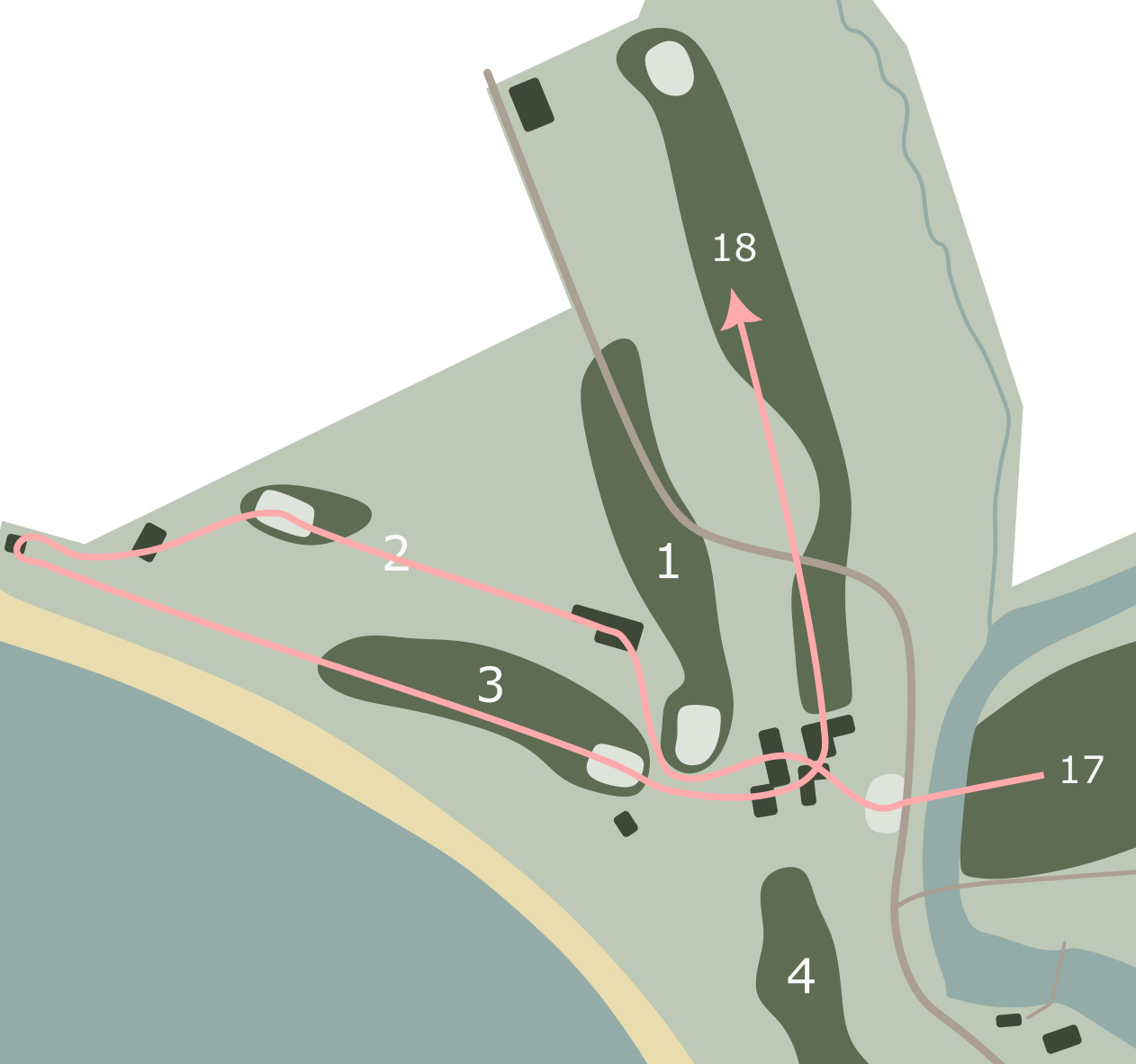

What I Wish I Could Change

Any course with a hundred year history should be exempted from nitpicks like this, but I will offer one anyway. I wish there were a way to return players to the sea before sending them home. The obvious way to do this would be, after the first hole, to send players straight to the fourth. Then after they finish the 17th, send them straight to the current second hole, then third, and finally finish via the 18th. Here, we’d allow players to leave the quieter section of the course and return to the wind and dunes one last time before heading in.

Unfortunately, my illustration shows how convoluted this routing would be. It just seems forced. I certainly wish there was a graceful way to do it, but I’m honestly fine with how the course finishes anyway. I just think it would be nice to return to the excitement of the early holes at the end of the round, but it is likely impossible without swapping the 18th and the first, which is really outside the realm of a reasonable ask.

Why Do I Think Dunaverty Offers Something that Typical Golf Destinations Cannot?

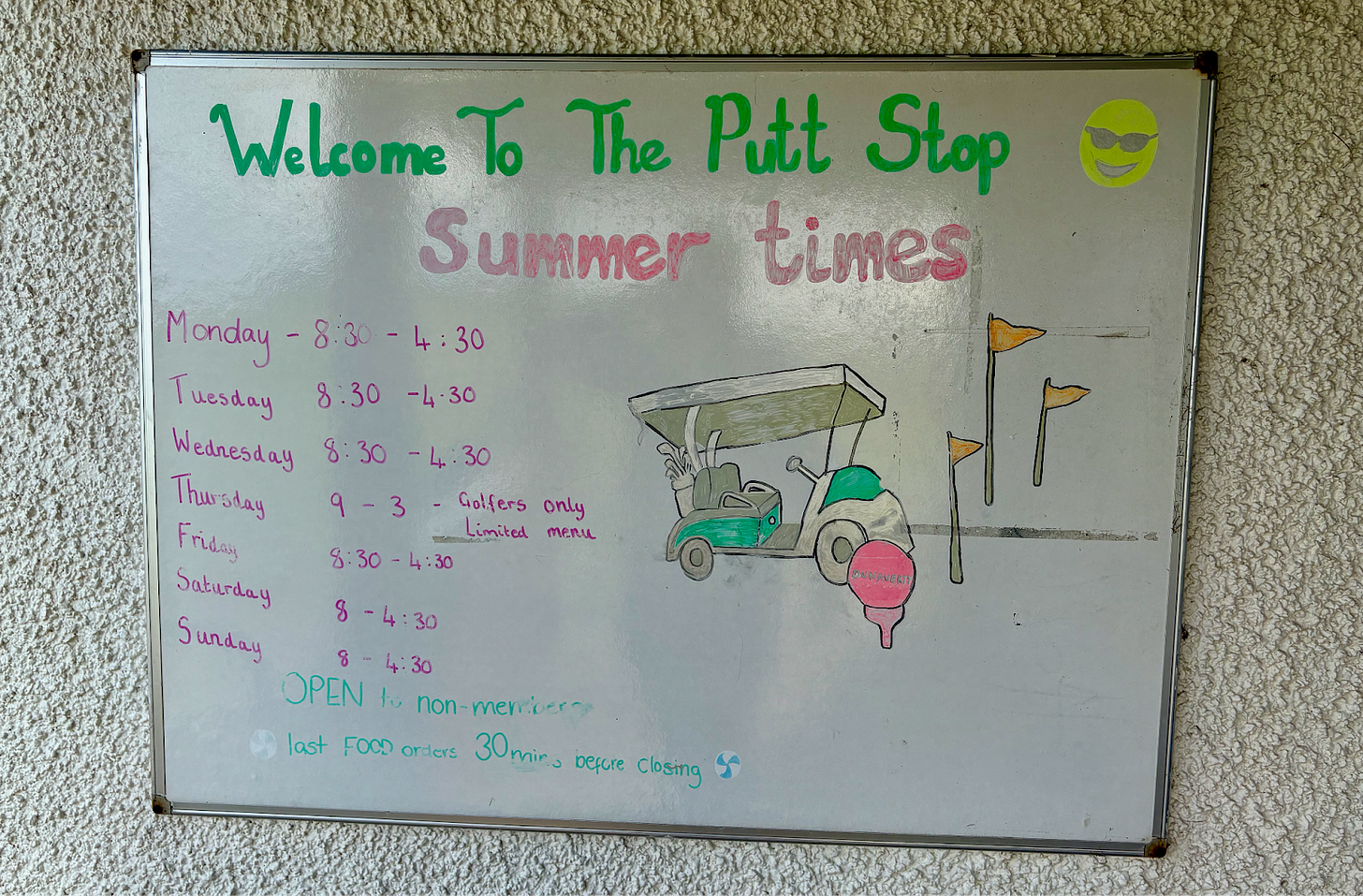

Finally, there is something about Dunaverty GC that I think is important, that is harder to put to words. Dunaverty has a sense of place that most other courses do not have. Where this stands out is at course’s restaurant. The restaurant at Dunaverty seems to serve the neighborhood as much as it serves the golf course. Everyone else in the restaurant when I ate there were locals, and many of them weren’t even there to play golf. They were just there to have a meal by the sea.

This has always been important to me. It is one of the first things I wrote about when I started writing about golf. At Machrihanish I was greeted after the round by a couple of very polite servers, and the dining area was rambunctious, with many tourists, along with a few groups of locals. At North Berwick, I was resigned to the club’s bar with members and their guests. At Dunaverty, however, I was surrounded by locals and given a table, where I was able to watch folks tee off to start and finish their rounds. I could see the folks playing on the course were almost exclusively locals, and many were older, and were very often women. I really appreciate this, but I’m not entirely sure why. There is nothing wrong with being a popular enough course to have lots of visitors. And all the courses I visited were very welcoming. I don’t want to be someone who is obsessed with an “authentic” aesthetic that makes no sense. I definitely understand the inherent contradiction of me, a tourist, discussing the tourist-to-local ratio of a golf course. It’s self-contradictory and I can’t explain it.

It’s just that courses like this – welcoming to others while still serving their community first – still affect me. Another place I think is really comparable is Pacific Grove. There is something about extremely special, yet imperfect courses with spaces welcoming the wider community, that really stand out to me. Pacific Grove has it, Northwood has it, and Dunaverty has it too. Perhaps it’s something to do with “third place”-ness.3 You are welcomed to Dunaverty GC in a way that you are not, or cannot, be welcomed in other places. Given the costs of travel, it seems like places like Dunaverty or Pacific Grove are defined by reasons not to visit more than reasons to make the journey. I’ll admit this isn’t a very coherent view, but at least it vaguely makes sense to me.

If you are looking for a reason to skip Dunaverty, you’ll find plenty: it’s hard to get to, the course has weak points, and the design doesn’t cater to most expectations. Still, I will be going back. I could play the first 14 holes at Dunaverty for the rest of my life, and I likely wouldn’t have much desire to leave. The combination of friendliness, accessibility, and affordability are at the heart of places I see as creating positive experiences, even if these places are imperfect.

Doak, Tom. The Confidential Guild to Golf Courses. Sleeping Bear Press, Chelsea, MI, 1996. Page 244.

I’m basing this assumption on three local weather stations that have nontrivial prevailing winds that all generally blow north or northeast:

Campbeltown Airport: https://www.windfinder.com/windstatistics/machrihanish

Rathlin Island: https://www.windfinder.com/windstatistics/rathlin_island

Oldenburg, Ray. The Great Good Place: Cafés, Coffee Shops, Community Centers, Beauty Parlors, General Stores, Bars, Hangouts, and how They Get You Through the Day. New York, Paragon House, 1989.

I fully understand you comment about a sense of place. Pacific Grove and Northland both have it. I guess to some degree I like the lack of perfection and the realness (if that's a word) of both.

Dunnaverty looks like another course I would enjoy. No golf trips to Scotland or Ireland in the near term.