A High Shot Hazard

We can revive the excitement of the Biarritz template by fighting back against the modern launch angles that have dominated it.

I want to talk about course design, and the possibility of reviving an older template that the modern game has all but eliminated. Specifically, I want to discuss the Biarritz template, but this discussion should apply to other hole designs generally as well. Designers typically limit themselves to traditional methods, and it has become harder to defend against the modern game. Modern launch angles have changed the way players approach courses. Many holes have effectively been beaten. Architects can and should fight back against these modern player tactics, and not simply by moving the tees back.

The Biarritz Template

I hesitate to even explain the Biarritz template here, as The Fried Egg has covered it so thoroughly.1 Simply put, a Biarritz hole is a long par 3, where the green notably has a deep valley in the center. Historically, the ball would be hit low with a driver, run onto the green, dive out of view through this dip, and then appear again on the back half of the green.

The long and short of it is this: due to modern ball flight trajectories, drivers no longer run out long distances, which this template uses. There is no more need to gamble against the dip in the green. Higher ball flight has mostly removed the excitement in how this hole is played.

New Technology is Not Necessarily Bad.

I will now say things that will be incredibly cliché to many. Every decade, driver distance increases, and every decade, the tees get moved back to compensate. I think a normal curmudgeonly reaction is the nerf now approach, but that likely won’t happen. People have been on both sides of this debate since before the gutty, as discussed by Wethered and Simpson back in 1929.2 One clear example of the effects of new distances is #13 at Southern Hills in Tulsa, which, for the PGA Championship, had its tees moved behind the #12 green, where players were teeing off directly over the other green. It was just so stupid.

Some of this improvement has been due to increased player fitness, sure, but most of it is just physics. It’s not magic. Manufacturers now make clubs that both get the ball higher in the air and land the ball at an optimal angle for roll or spin. The reasons for this were discussed in Golf Digest in 2019:

Still, there also is some serious physics happening here. As club technologies have allowed for the center of gravity to get lower (leading in some cases to higher launch), an iron can then be designed with a stronger loft that takes advantage of that higher launch. Faster ball speed with the same or higher launch means more distance and a better landing trajectory. That’s why when you start seriously testing potential new irons, don’t just look at distance. Use the modern technology of a launch monitor to assess those landing angles. Ideally, you want your shots to have a landing angle of more than 45 degrees for best performance coming into a green.3

While tees have been moved back year after year, and green speeds have nearly doubled since the 1980s, golf course architects have made no substantive change to make these longer and higher approach shots more risky. We haven’t created new counter-measures to harness all this additional momentum, and convert it into a hazard for the player. Instead, designers continue to require additional energy by merely elongating holes.

Discourage High Shots by Changing Their Risk Profile

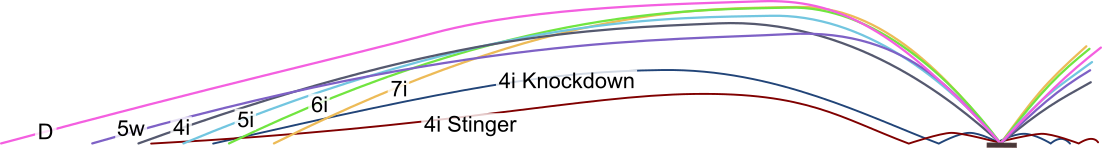

Ideal launch angles can be countered, we just choose not to counter them. Trackman, a leading launch monitor manufacturer, has released data showing that professionals now flight shots from nearly every club to this same 30-yard height, and only driver and 3 wood have a landing angle below 45 degrees:4

I’m proposing a new greenside hazard that kicks high shots far from their intended landing zone, but leaves low shots generally unmolested. I propose calling it a “high hazard,” referring to the high launch angle and trajectory of the modern clubs.

The idea is fairly simple. At times when a course designer would prefer players to use low running shots to the green, such as with the Biarritz template, the designer can use a rigid surface, such as railroad ties, to dramatically increase the probability that a high shot in will bounce wildly, but a low shot will skip over it as though the ties are just hard turf. Here is an illustration of the idea:5

Every golfer has encountered this phenomenon: a good shot hits a cart path and kicks to a completely different landing area. My argument is that we should harness the ball’s energy via this unique occurrence to counter power in hole design.

More specifically, I am suggesting using “sleepers,” as they’re called at Prestwick, as this type of greenside hazard. A sleeper is a series of wooden planks or railroad ties, used to hold back earth, often above a bunker. They are not new, and already exist fronting bunkers on some of the oldest courses on earth.

What I propose, however, is that the architect turns the sleepers nearly flat and removes the sand altogether. Use these wooden planks as a hazard simply because they are rigid, and can deflect the ball more powerfully than turf. Let’s look at a specific example of how this would work, and how it would change how a hole plays.

#3 at Chicago

This is #3 at Chicago Golf Club. It’s an archetype Biarritz template. The template features a firm green with a deep valley in the center, and the hole is almost always placed on the back tier. The men’s tees are officially 219 yards, but I’ve marked the distances from the tee boxes to the center of the back of the green. One can see here how this hole is famous for the excitement of a long, running shot disappearing as it drops into this valley, and then reappearing as it approaches the hole. However, this no longer happens. Why not? Because the high shot dominates the payoffs in a game-theoretic sense.

Here are the two scenarios: with a high shot that misses left or right, the player is likely in a bunker. With a low, running shot the player might not even reach the back of the green, but if the shot misses as before, the result is exactly the same as if they had used a high shot. In fact, the player who hits the low shot is more likely to end up in a bunker, because any miss that crosses a bunker will end up in it. There are even more negatives when playing a low shot, because unlike with a high shot, the front bunker will always be in play.

A New Design

Let’s look at an alternative version of the same hole, but with sleepers as high-shot hazards:

Again, let’s look at the same two scenarios. Suppose a high shot just misses the green left or right. If it hits the sleeper, it will kick wildly away from the hole, leaving a long pitch back to the green. In contrast, a low shot that just misses should run across the sleeper to the adjacent turf, leaving an easy up-and-down. This creates a real risk for players using a high launch angle, a risk that can be avoided by using the kind of low, running shot that the hole was designed for.

This brings a tangible benefit to the shot that the architect wants to reward. We can again have the ball dip below the ridge and then surface back up above to the back. Importantly, however, the change doesn’t remove the option for players to play a high shot, it just changes its risk profile.

Stinger vs Knockdown

A second change I’ve made to this hole is adding a more forward set of men’s tees. This is to leave open the option for higher handicap players to simply play a knockdown runner into the front of the green. Scratch players can be tested on their stinger, or quail shot as it was known in a previous era.6 But since the lofts and launch angles of clubs have changed and drivers no longer run out for 20 yards, it seems sensible to add a forward tee to allow higher handicappers to play the easier knockdown shot and get the ball running across the green. Whereas a stinger is a full shot hit with low spin and a stunningly low launch angle, a knockdown is simply a half-shot made with a longer club. It's easier in technique, but still requires the player to think strategically on the tee. Allowing the knockdown for higher handicappers will require removing some moderate distance, but the goal is still to test the shot-making of a running shot, not just a stinger per se.

Concerns and Potential Benefits

First off, I think it’s important to note that this new hazard technically does not change the difficulty of the hole. It has merely converted some of these existing hazards from one type to another. The total surface area of the hazards has actually gone down. Players can still play the same high shot as before, but with a change in results for a missed shot.

The obvious first concern will be aesthetics and traditions, and I certainly have some sympathy for this. Many of the folks over at Golf Atlas are not fans of the look of some railroad ties,7 but Pete Dye embraced them and they are a hallmark of his course design.8 I certainly don't think they harm the aesthetics of a course, but I'm sympathetic to those who may be concerned.

Some will complain about what happens if a player has to play over them, or if the ball comes to rest on them. They are artificial and can cause confusion. These issues are all trivially solved via local rules, and courses are certainly free to reject this concept. It's perfectly reasonable to expect players to hit off of wooden boards in some instances. Any objection to artificial hazards, as such, must explain away the pavement on the Road Hole, where players are required to hit off the road itself. I could see some clubs offering a free drop, but I see no loss of the spirit of the game here.

My first real concern is drainage. Modern courses typically use drainage under the green to help it play firmer and faster, but most don’t have this drainage in front of the green. I find this, combined with regular irrigation, can lead to soggy sections below many greens, with dry, firm green above. Modern clubs have mostly overcome this by stopping the ball tight at the landing spot. This combined with embedded ball relief has removed this issue altogether, but this wet-dry dynamic will be problematic for any course trying to encourage a low shot.

One benefit from this type of hazard, however, could be giving architects more direct access to drainage pipes. I haven’t worked on designing any courses, and the only information I have on the subject of architecture comes from books, but it seems plausible that a hinged sleeper laying against an embankment could trivially be turned into a door providing physical access to drain pipes routed under such a hazard. I may be way out of my depth here, but it seems to me that having a door under the green could be a very good alternative to earthmoving when looking for leaks and/or repairing or replacing pipes. I welcome any feedback from golf course architects willing to reach out and let me know if this is sensible or just nonsense.

Generalizing to Any Course

While the Biarritz template is a favorite of C.B. MacDonald fans, the concept of a high-shot hazard needn’t be reserved for templates. Any time lofted shots come into play, sleepers can be used to encourage, but not require, players to take a non-standard approach.

This type of hazard could especially add character to holes that play into the wind, where shots balloon regularly. They could be used to spice up downhill approaches. They could even be employed to caution against playing too aggressively around doglegs that modern clubs have successfully circumvented.

The times when I most enjoy golf are those when I see a hole layout asking me to do more than just strike the ball well at a distance I’ve trained for. I appreciate it when an architect asks me to consider position and tactics over the dominant bomb and hack strategies that are commonplace. I think increasingly optimized ball trajectories and swing speeds can be countered with high-shot sleeper hazards. Is it a gimmick? I’m sure some will think so, but I don’t. In the way that someone practicing judo will use their opponent’s weight and momentum against them, I think this type of high-shot hazard can focus all the added power that technology has given us, and make us think twice about how we use it. Whether it be a wooden sleeper, a section of flat exposed limestone, or even an intentionally positioned cart path, a high shot hazard can make us all a bit more cautious about mechanically optimizing every shot for maximum distance and efficiency.

Thank you for reading Wigs on the Green. I publish these articles to promote the golfcourse.wiki project. This project is to create a central, publically accessable resource for golf architecture and local knowledge of every course on earth. Adding your home course will help the project, and make your course more accessible to others in your area.

Johnson, Andy. “The Templates: Biarritz. A history and analysis of C.B. Macdonald's Biarritz template.” The Fried Egg. Jul 7, 2016.

Wethered, H.N., and T. Simpson. The Architectural Side of Golf. Classics of Golf, 1929.

Johnson, E. Michael, and Mike Stachura. “Golf equipment truths: Iron faces are nearly as fast as a driver’s. Here's why.” Golf Digest. Nov 8, 2019.

TrackMan. “TrackMan Average Tour Stats.” TrackMan University. blog.trackmangolf.com, Jun 6, 2014. Via Archive.org archive from Jul 6, 2015.

These shot trajectories right-shifted arcs based on this image:

The image was aquired via:

Perrey, Curtis. “You are approximately between 50 and 60 metres from the pin in a game of golf. How can the biomechanics of the pitch shot be maximised to get the ball close to the hole?” HLPE3531 Blog. Apr 22, 2013.

However, this was not the origin of the image. The citation given there is:

Golf Research and Experience. http://web4homes.com/golf/. 2013.

This site is no longer accessible, and the best I could find is this link via Archive.org, which doesn’t include the image itself. Suffice it to say, I’m not trying to argue these are exact shot measurements, just illustrate that common shot landing angles are much more severe than one might assume.

Here, I’m referring to Jimmy Demaret’s “quail shot” as equivalent to a “stinger.” This is my own pet theory, but I feel comfortable conflating the two as essentially the same shot based on both the description of the shot and the unique muscle requirements involved. Here is the description found in Penick’s Red Book (citation below). Note Demaret’s forearm strength:

Jimmy had the forearms of a giant and could hit that little ball in what he called a “quail shot” that didn’t go more than two or three feet off the ground. (Penick, 132)

Tiger Woods specifically discusses his forearm strength in developing his shot (again, this citation is also below):

I developed this low-flying tee shot in the late ’90s (Woods)

It wasn’t an easy shot to master. I had to get stronger, particularly in my forearms, to be able to cut off the swing just after impact to hit this shot. (Woods)

I think it would be shocking if Woods was not familiar with Penick’s book, and his development of the shot would have corresponded pretty well with the book’s publication in the early ‘90s, with Woods mastering the shot in the late ‘90s.

Penick, Harvey. Harvey Penick's Little Red Golf Book : Lessons and Teachings from a Lifetime in Golf. Collins Willow, 1993, London. pp. 132.

Woods, Tiger. How Tiger Woods' stinger has evolved over his career. Golf Digest. Jul 15, 2020.

Gaskins, Chip. “Railroad ties in bunkers...” Golf Club Atlas. Question in Discussion Group. Nov 9, 2008.

Schultz, Jack. “Golf Course Design Identifiers — Pete Dye” Golf on the Mind. Mar 13, 2017.

This is madness. I like it.